Hard opinions from a happy pessimist on movies from any era, any country, and any quality.

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

The Essentials, Part 2: Screenwriting

Since I'm trying to come up with a comprehensive list for beginning film studies students, I've decided that there will be no repeats on this list. If you think something from the classics list should be in this list, yet you don't see it, that's because you've already been told to watch it. I will be doing a full list of foreign films in the future, and so I am going to try to keep them at a minimum until I devote a post solely to them.

For this list on screenwriting, I am going to focus on films where the writing is not only strong, but it is also successful in conveying the kinds of things you learn in a screenwriting course, such as character development, plotting, pacing, dialogue, moral and social issues, etc.

City Lights (1931)

Just because there's no spoken dialogue, that doesn't mean a film didn't have a writer. Chaplin's City Lights is a beautiful, heartbreaking love story acting like a simple mistaken-identity comedy. The complexity of its writing sneaks up on you in the third act, when the poor tramp is finally recognized by the blind girl selling flowers on the side of the road. When she realizes the kind of sacrifice the tramp has really made, it's hard to keep your eyes dry. This is one of the best, and earliest, examples of the set-up/pay-off screenplay formula. Almost everything that happens in the first half of the movie is referenced again in the latter half, and Chaplin's tight pacing and structure makes this one of his most watchable films.

M (1931)

M deals with moral ambiguities that even most modern films won't touch. Here we have a man who has a compulsion, a sick compulsion, to murder children. He is terrified of his own desires, and with each murder he commits, the more insane with guilt and anger he becomes. We see a courtroom scene unlike any other, presided over by the criminal underworld, where the guilty judge the guilty, and the moral ambiguities of this scene are constantly observed and understood by the characters. This is a triumphant film because it investigates the darkness inside all of us and passes no judgment. It merely watches these people interact with one another, and it is a bold vision.

Double Indemnity (1944)

The frame narrative works in Double Indemnity because of the stylistic formula of the Noir. A dissociated voice, somewhere in the clouds, tells us what happens to the people we're watching with an unbelievable clarity. The voice knows where this story goes, he's seen it before, and we're just along for the ride. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler's script is one of those classic three-act screenplays that delivers exactly as the formula requests, but delivers so well that we forget how many times we've seen the story.

High Noon (1952)

Carl Foreman's screenplay for High Noon was written as a direct response to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Foreman was blacklisted in Hollywood as a communist, and this screenplay is his reaction to his persecution in the midst of the Cold War. Marshal Kane, played by Gary Cooper, is out against the world and there isn't anybody who can help him. The film takes place in real time, and we get a snapshot of Kane's existence, alone and scared and dark, and all of this is part of a bigger picture--the world, in 1952, was scared and desperate. Foreman writes from a place of fear, and Kane, cornered by the opposition, can do only what he knows how--kill.

The Graduate (1967)

Benjamin Braddock is a product of the fifties trying to make sense of the changing times. He's just graduated college and he's looking for a place in the world. He holds on to his youth, to his need for a maternal figure, to a person who has already found success and comfort. He knows he can't love her, but he does. It takes the youth of her daughter and the unknown future that she represents for Braddock to grow up. He breaks through his youthful need for a security blanket with his young love, but, in that final, brilliant shot, Braddock remembers that the future is unknown. Where is he going now? Buck Henry's script perfectly encapsulates that feeling of unease that surrounds a time of great change. His movie is the late 1960s.

Scenes from a Marriage (1973)

Scenes from a Marriage chronicles the slow disintegration of a marriage. It begins with the Marianne and Johan's friends announcing their divorce. Marianne says that'll never happen to her own marriage. Johan isn't so sure. This is the beginning of a decade-spanning conversation that covers the mountains and valleys of a long-term relationship. Bergman investigates marriage with an honesty that I've never seen before. These characters rip one another apart, but we are never exposed to melodrama or easy answers. There are no bad guys, just two people getting to know one another better than they know themselves.

Paris, Texas (1984)

Sam Shepard wasn't done with the screenplay when production started on the Palm D'or winning Paris, Texas. The story follows Travis, an amnesiac wanderer who is picked up by his brother and slowly comes to remember who he is and what he cherishes the most. The screenplay is about family and memory and love and anger and guilt and, in the end, nobody quite gets exactly what they want. This movie contains, what I think, is the best monologue ever written. Watch it.

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Do our past actions define us, or are we defined by our promises of the future? What is guilt if it isn't our conscience trying desperately to define us as unworthy? Woody Allen's masterpiece, Crimes and Misdemeanors, addresses the big questions. What is true justice? In a world of murder and rape and disgust, what is true evil? Aren't all living things evil by default? Is there a spectrum of the crimes that we commit, or does everything we do rattle with equal significance? This film deals with guilt and anger and despair in a more mature and honest way than I have seen in any other film. A truly powerful piece of filmmaking.

Breaking the Waves (1996)

Lars Von Trier has made a name for himself with his stories about women in dire circumstances. They often end tragically, and Breaking the Waves is no exception. However, unlike some of his later films, Breaking the Waves doesn't have some sort of film gimmick, like musical numbers or minimalist set design. No, this film is just pure story, pure writing, and it is devastating. Trier's recreation of the passion play is moving and tragic, but in its final moments, it is transcendent.

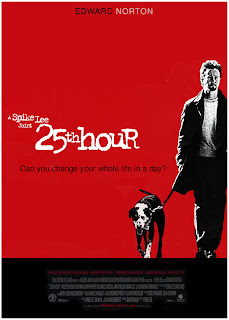

25th Hour (2002)

David Benioff's 25th Hour is about post-9/11 New York. Of course, the plot surrounds Monty Brogan as he lives his final day before going to prison for felony drug trafficking, but this story is really about how America deals with difficult times. Monty is angry and frustrated that his life has ended up the way that it has, but he is also responsible. He got greedy, he took things that didn't belong to him, he made decisions, big decisions, for other people. He embraces everybody of every color and creed, but he doesn't love them equally. In fact, he equally despises them. Monty has dreams and ambitions that he'll never be able to achieve because of his charred past. He blew it, he knows it, and he's trying to pick up the pieces.

What are some of your favorite screenplays?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

__BreakingTheWaves(1).jpg)

Great list. I wish you could team-teach the Screenwriting class with me.

ReplyDeleteThanks for these comprehensive recommendations. I will definitely take these into consideration the next few weeks! If only they were all on Netflix instant stream!

ReplyDeleteWe need to spend more time watching movies made after 1960.

ReplyDeleteAdaptation seems obvious, but I'll list it anyway. Once the initial cleverness wears off (though I've seen it over half a dozen times, and it still hasn't for me), the deeper significance of every conversation, every action and every conclusion hits with a startling power. Many of Charlie Kaufman's other films exhibit similar strengths, but it's here that, I feel, they are most apparent and enjoyable.

ReplyDelete