Hard opinions from a happy pessimist on movies from any era, any country, and any quality.

Monday, May 28, 2012

Movie Review: Men in Black 3

What has changed since 1997? Certainly the scope of what computer effects are able to accomplish has shifted. We've grown accustomed to the things that used to wow us. For instance, that final reveal at the end of Men in Black where the galaxy is all part of a game of marbles was immensely awe-inspiring when I saw that film in the theater. Today, that scene would not be enough to wow me. We've grown jaded, and this is not good for Men in Black.

The first film put a lot of stock in special effects wizardry and make-up. It is one of the rare occasions where a big-budget blockbuster's special effects were used to make jokes even funnier. It is, in my opinion, the first film to truly integrate computer effects in a way that served the film and made it better. And yes, I've seen Forrest Gump.

Men in Black had a huge effect on me when I was younger. I was introduced to a world that was very similar to my own, yet it contained all of the nightmares and dreams that, at the age of seven, only I could see. I loved that aliens were real and living amongst us. I loved the idea of a disguise, of a secret agent, and of having gadgets that accomplish impossible, amazing things. The film played with the importance of size. The "midget cricket" serves as an excellent taste of foreshadowing, and is one of many clever, inventive storytelling devices used in the film.

Will Smith's Agent J truly goes through a narrative arc in the film--beginning his story as a cocky and world-weary NYPD officer and ending the film as a man who knows there's always mystery left in the universe. He grows to truly care about his partner and the planet that he is saving. Tommy Lee Jones's Agent K is a delightful play on the classic Jones character, looking stone-faced into the absurd and asking it to follow arbitrary rules. He, too, follows a satisfying arc where he grows from being a jaded intergalactic detective to a happy, blissfully ignorant retiree. Men in Black is one of those great Hollywood blockbusters that just works. The chemistry between the actors, the visual effects, the world-building, and the story structure just seem to effortlessly click.

So what went wrong with Men in Black II?

Well, this poster sums up a lot of it. Look at Agents K and J sitting in those chairs and holding those guns. Those chairs are featured in a famous recruiting scene from the first film. The guns are featured from the finale of the first film. Neither of those things appear in the second film. However, approximately everything else does. The second film seems to exist for the sole purpose of retreating the first film. The coffee-pouring insects that worked so well as an element of world-building? Lets cast them as crucial, plot-progressing characters. The dog with a couple of lines that serves as comic relief during the most tense section of the first film? Lets improbably make him an agent and make him spout out hundreds of desperate attempts at catchphrases.

Also, the first film had a fantastic, disgusting villain in Vincent D'Onofrio's cockroach. He was gross, manic, mean, offensive, and exactly the kind of villain these guys would have to fight on a weekly basis. He was a roach, he was vermin, and he wanted revenge on a planet that treated his family like scum. His motive is built into the audience's everyday life. It's a brilliant conceit. Lara Flynn Boyle's sexy plant-vine villain is...less brilliant. First of all, her minion is the instantly dated joke of Johnny Knoxville acting, and second of all, she's a lingerie model who doesn't seem to have any other motive that just being evil.

The second film is sloppy. It resurrects Agent K because it needs to, it uses a sexy villain because marketing executives asked it to, it overindulges itself on previously used side-characters because it didn't trust the creative team to create new ones, and it seems to only exist because somebody out there liked the talking dog.

So why even bother with Men in Black 3? If the second film was already desperately clinging onto its franchise roots for inspiration, how must the third film fare?

Well, surprisingly, it's actually pretty good.

What the third film carries with it is the wisdom gained from the dreadful sequel. Gone are the petty references to the first film. Gone is a distractingly over-sexualized villain (unless you find the man in the above picture hunky), and gone is all of the sloppy plotting that comes with bringing back an essentially killed-off character. Which is funny, because this film's plot is bringing back a killed-off character.

I'll make it short, Jemaine Clement's hilariously cocky Boris The Animal escapes from Lunar Max prison and goes back in time. In 1969, Boris kills Agent K. Agent J, now a senior agent after 14 years of experience, is the only person who remembers Agent K from the present, so he too goes back in time to stop Boris from killing K. It's not a particularly creative premise, but the execution is fantastic.

Before I go into the performances and the excellent plotting, I have to point out the time-travel scene in which Will Smith's Agent J jumps off the Chrysler building. It is one of the greatest, most imaginative special effects shots I've seen in quite some time. See the movie just for that shot alone.

Anyway, Agent J makes it back to the sixties and the usual time-travel hilarity ensues. Andy Warhol is a bored, undercover MiB agent! Cops are racist! The Rolling Stones aren't old! I thought, for a few minutes into the sequence, that the film was going to roll over and just deliver cheap gags based around the time-travel conceit. But I was wrong. In fact, the film does very little in the form of cheap gags. When it tips its hat to the original film, it does so with background action. We see the site of the finale of the end of the first film deep in the background during a chase sequence, for instance. Nothing too forthright, nothing distracting. The film is just focused on the story it is telling, and it is focused on the characters who must make their arcs.

Replacing Tommy Lee Jones this time around (Jones is in the film, but he probably only worked for a weekend) is Josh Brolin, who does an absolutely remarkable impression of Tommy Lee Jones. It almost transcends imitation and turns into downright brilliance. Brolin disappears into the role and adds an all new dimension to the character of Agent K. I was shocked by Brolin's performance, and it gave the film a whole new weight that I haven't seen in the other two films. Also joining the cast is a character named Griff who can see every possible future and past of any particular scenario. He is played with awe-shucks sincerity by A Serious Man's Michael Stuhlbarg. Griff too adds to the emotional spectrum of the film. He adds the whimsy that was absent in Men in Black II because Agent J was no longer new to the club.

I hesitate to give you any more information than this, for fear I'll spoil some of the last act, which is a magnificently constructed set-piece that ends on an uncharacteristically emotional note for the series.

Was Men in Black 3 necessary? Not really, but it certainly works much better as a direct sequel to the first film than the second, as if the filmmakers too are embarrassed by that half-hearted entry. This film is funny, engaging, and surprisingly poignant. If you didn't like the first film, this one won't convert you, but if you too were disappointed by the second film's sloppy handling of the characters, then I think you should check this one out. It is an excellent way to spend your afternoon.

I give Men in Black 3 7.5/10 grumpy Josh Brolins

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

The Essentials, Part 3: The Strange

I've been asked over and over again what I find to be the strangest and darkest movies I've ever seen. Even though these sorts of lists will always be subjective, I find it even more subjective to list the weirdest movies I've ever seen. I mean, what I find strange could be something you find totally normal, and vice versa. So instead of just picking out movies that I find weird, I'm going to pull out, as I have before, films that I think used their bucking of trends and formulas to their advantages. These are the films that I would teach a class based around experimentation and a willingness to convey images and ideas not often associated with "the mainstream." In other words, this is probably the closest we're going to get to a list of my truly favorite films.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali's famously bewildering 1929 short film relied heavily on Freudian free-association for its screenwriting and also relied on nightmarish images for its shoot. The film is probably most famous for its eye-slitting scene (pictured above), but I admire this film for going out of its way to freak out its audience. I would even go so far as to call this the first truly successful horror film of all time. Perhaps I am cheating by including this film, seeing as its a short and all, but I really can't think of a better way to introduce experimental and surrealist filmmaking without subjecting a class full of students to Buñuel's madness.

Freaks (1932)

Tod Browning's infamous 1932 film put actual circus "freaks" front and center in the cast. This film came out before the Hollywood morality code, and because of this you'll see much more disturbing imagery and ideas in this film than any Hollywood film made in the 1940's or 1950's. Upon its release, Freaks some serious controversy for its unusual subject matter and frank depictions of deformity and human suffering. And, for 1932, this was an astoundingly bleak and original vision. Over the years, Freaks has achieved a strong cult following for both its subject matter and for the novelty of the time in which it was made.

Cat People (1942)

Jacques Tourneur made Cat People because he was fascinated by America's fear of female sexuality. The film focuses on Irena, a woman who is terrified by her own animalistic desires. Animals constantly call out to her. Sometimes she blacks out and has no idea where she was. She is afraid to sleep with her husband because of what might happen. Before long, Irena is transforming into a wild animal and killing whatever gets in her way. She cannot control her body or her thoughts. Tourneur's film is not only a landmark horror film with its willingness to let the true scares happen offscreen, but it is also perfect for a college class with all of its (for its time) progessive themes and ideas.

Pickup on South Street (1953)

Many mid-twentieth century cult films play with the subject of human sexuality in obscure and interesting ways. Pickup uses the imagery of a pickpocket on the prowl as a symbol for men who steal women's hearts. It's not a subtle bit of artistry, but the film uses this motif in interesting ways. Skip, the pickpocket, steals Candy's wallet -- a wallet which just happens to hold important communist information--and begins a complicated game of cat and mouse. This is one of Sam Fuller's Noir exercises, and he uses the genre's German Expressionistic roots to his advantage. A simple espionage film turns into a statement about human sexuality and sexual politics in the 1950's.

8½ (1963)

Fellini's films are often surreal, but few of them are able to implement their surrealist elements as organically as this film. A filmmaker struggles with the weight of expectation as he tries to film a movie that he has not yet written. He is surrounded by critics, reporters, and fans who all want to be a part of his newest masterpiece, but he has no idea how the movie will end. Fellini's film is a huge influence for the Cate Blanchett section of Todd Haynes's I'm Not There, and for good reason--this film is one of the great, uncompromising works of fiction that describes just how hard it is to live the life of the artist.

Persona (1966)

Persona not only plays with ideas surrounding identity and fame and mental illness, but the film itself is unusual in the way it was written, shot, and edited. The film concerns a mentally ill movie star who moves to a secluded island with a nurse. Most of the first half of the movie is a monologue from the nurse, who is trying to cut the silence left by the movie star with stories of her past. However, at the halfway point, the film switches focus. The film literally breaks, the identities switch, and confusion ensues. This film was a huge influence on the production of Robert Altman's 3 Women and David Lynch's Mulholland Drive.

Brazil (1985)

This film has nothing to do with Brazil, unless you count its soundtrack. Terry Gilliam's strange, surreal, and hilarious take on the future is one of the most unique film experiences that you can find. It is George Orwell seen through the lens of Franz Kafka. It is the nightmare of bureaucracy reaching its logical conclusion. The film concerns a case of mistaken identity that gets very, very out of hand. Gilliam's effects work mixed with his amazing ability to turn everything into a strange, dreamlike moment of surreality makes Brazil his crowning achievement.

Waking Life (2001)

Richard Linklater has made his fair share conversation movies. These films are usually just focused on listening to people talk about interesting and strange things they've seen in their lives. Slacker and Before Sunrise are probably his most famous conversation movies. However, I find Slacker kind of tedious and annoying because it seems to only have on perspective and that perspective is quite young. With Waking Life, Linklater has matured a little bit and decided to let in all sorts of points-of-view. The subjects discussed range from talk about dreams and death to talk about cell regeneration and governmental ethics. It's all over the map, and it meanders with its deliberate pacing. Fortunately, on top of the engaging conversations is a fascinating rotoscope animation that keeps the visuals of the film fresh and dynamic.

Inland Empire (2006)

If you've been keeping up with this blog for any amount of time, you'll know that I have a bit of a thing for David Lynch. And Inland Empire is, in my opinion, his greatest film. It is everything he has been working toward. He plays with identity, gender, fame, fiction, dreams, death, violence, betrayal, and love in this film with equal success. It is strange, scary, funny, and spellbinding. I believe there is no other film that could end a course on "weird" movies. This is the culmination of all the experiments that came before it.

What did I miss? What are some of your "strangest" films?

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

The Essentials, Part 2: Screenwriting

Since I'm trying to come up with a comprehensive list for beginning film studies students, I've decided that there will be no repeats on this list. If you think something from the classics list should be in this list, yet you don't see it, that's because you've already been told to watch it. I will be doing a full list of foreign films in the future, and so I am going to try to keep them at a minimum until I devote a post solely to them.

For this list on screenwriting, I am going to focus on films where the writing is not only strong, but it is also successful in conveying the kinds of things you learn in a screenwriting course, such as character development, plotting, pacing, dialogue, moral and social issues, etc.

City Lights (1931)

Just because there's no spoken dialogue, that doesn't mean a film didn't have a writer. Chaplin's City Lights is a beautiful, heartbreaking love story acting like a simple mistaken-identity comedy. The complexity of its writing sneaks up on you in the third act, when the poor tramp is finally recognized by the blind girl selling flowers on the side of the road. When she realizes the kind of sacrifice the tramp has really made, it's hard to keep your eyes dry. This is one of the best, and earliest, examples of the set-up/pay-off screenplay formula. Almost everything that happens in the first half of the movie is referenced again in the latter half, and Chaplin's tight pacing and structure makes this one of his most watchable films.

M (1931)

M deals with moral ambiguities that even most modern films won't touch. Here we have a man who has a compulsion, a sick compulsion, to murder children. He is terrified of his own desires, and with each murder he commits, the more insane with guilt and anger he becomes. We see a courtroom scene unlike any other, presided over by the criminal underworld, where the guilty judge the guilty, and the moral ambiguities of this scene are constantly observed and understood by the characters. This is a triumphant film because it investigates the darkness inside all of us and passes no judgment. It merely watches these people interact with one another, and it is a bold vision.

Double Indemnity (1944)

The frame narrative works in Double Indemnity because of the stylistic formula of the Noir. A dissociated voice, somewhere in the clouds, tells us what happens to the people we're watching with an unbelievable clarity. The voice knows where this story goes, he's seen it before, and we're just along for the ride. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler's script is one of those classic three-act screenplays that delivers exactly as the formula requests, but delivers so well that we forget how many times we've seen the story.

High Noon (1952)

Carl Foreman's screenplay for High Noon was written as a direct response to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Foreman was blacklisted in Hollywood as a communist, and this screenplay is his reaction to his persecution in the midst of the Cold War. Marshal Kane, played by Gary Cooper, is out against the world and there isn't anybody who can help him. The film takes place in real time, and we get a snapshot of Kane's existence, alone and scared and dark, and all of this is part of a bigger picture--the world, in 1952, was scared and desperate. Foreman writes from a place of fear, and Kane, cornered by the opposition, can do only what he knows how--kill.

The Graduate (1967)

Benjamin Braddock is a product of the fifties trying to make sense of the changing times. He's just graduated college and he's looking for a place in the world. He holds on to his youth, to his need for a maternal figure, to a person who has already found success and comfort. He knows he can't love her, but he does. It takes the youth of her daughter and the unknown future that she represents for Braddock to grow up. He breaks through his youthful need for a security blanket with his young love, but, in that final, brilliant shot, Braddock remembers that the future is unknown. Where is he going now? Buck Henry's script perfectly encapsulates that feeling of unease that surrounds a time of great change. His movie is the late 1960s.

Scenes from a Marriage (1973)

Scenes from a Marriage chronicles the slow disintegration of a marriage. It begins with the Marianne and Johan's friends announcing their divorce. Marianne says that'll never happen to her own marriage. Johan isn't so sure. This is the beginning of a decade-spanning conversation that covers the mountains and valleys of a long-term relationship. Bergman investigates marriage with an honesty that I've never seen before. These characters rip one another apart, but we are never exposed to melodrama or easy answers. There are no bad guys, just two people getting to know one another better than they know themselves.

Paris, Texas (1984)

Sam Shepard wasn't done with the screenplay when production started on the Palm D'or winning Paris, Texas. The story follows Travis, an amnesiac wanderer who is picked up by his brother and slowly comes to remember who he is and what he cherishes the most. The screenplay is about family and memory and love and anger and guilt and, in the end, nobody quite gets exactly what they want. This movie contains, what I think, is the best monologue ever written. Watch it.

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Do our past actions define us, or are we defined by our promises of the future? What is guilt if it isn't our conscience trying desperately to define us as unworthy? Woody Allen's masterpiece, Crimes and Misdemeanors, addresses the big questions. What is true justice? In a world of murder and rape and disgust, what is true evil? Aren't all living things evil by default? Is there a spectrum of the crimes that we commit, or does everything we do rattle with equal significance? This film deals with guilt and anger and despair in a more mature and honest way than I have seen in any other film. A truly powerful piece of filmmaking.

Breaking the Waves (1996)

Lars Von Trier has made a name for himself with his stories about women in dire circumstances. They often end tragically, and Breaking the Waves is no exception. However, unlike some of his later films, Breaking the Waves doesn't have some sort of film gimmick, like musical numbers or minimalist set design. No, this film is just pure story, pure writing, and it is devastating. Trier's recreation of the passion play is moving and tragic, but in its final moments, it is transcendent.

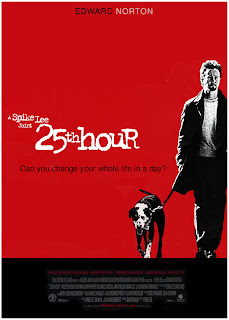

25th Hour (2002)

David Benioff's 25th Hour is about post-9/11 New York. Of course, the plot surrounds Monty Brogan as he lives his final day before going to prison for felony drug trafficking, but this story is really about how America deals with difficult times. Monty is angry and frustrated that his life has ended up the way that it has, but he is also responsible. He got greedy, he took things that didn't belong to him, he made decisions, big decisions, for other people. He embraces everybody of every color and creed, but he doesn't love them equally. In fact, he equally despises them. Monty has dreams and ambitions that he'll never be able to achieve because of his charred past. He blew it, he knows it, and he's trying to pick up the pieces.

What are some of your favorite screenplays?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

__BreakingTheWaves(1).jpg)