Hard opinions from a happy pessimist on movies from any era, any country, and any quality.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Underrated AND Misinterpreted: A.I. Artificial Intelligence

People often unfairly criticize Steven Spielberg for "changing" Stanley Kubrick's original vision of A.I. Artificial Intelligence. I've even said this myself. For years, I thought that A.I. was an almost-masterpiece. That it was just a few tweaks away from being one of the great science fiction films. As I've gotten older, I am realizing more and more that A.I. is not only a great movie, but it is one of the most horrifying, non-sentimental films Steven Spielberg has ever made. And it is certainly, in my opinion, his finest foray into "serious" filmmaking.

I know what you're thinking. Plenty of you probably saw the title and slapped your foreheads. "No, Cameron. No. That's the movie where Spielberg raped Stanley Kubrick."

Actually, Kubrick always intended for Spielberg to direct the film. The two were very close and they admired one another's work. Kubrick always saw Spielberg as the perfect fit for this film because of his gift with effects and child actors. And, as Kubrick got older, he shied further and further away from taking directing gigs for fear he'd take too long setting up shots of people walking through doors. He acknowledged Spielberg as the populist, and he knew the film needed to run through a filter before entering the world. Even Kubrick found the subject matter a little too dark for his own sensibilities.

In his last years of life, Kubrick labored over robot designs, conceived of what future America would look like, and sketched storyboards for the most crucial scenes. He also developed several drafts of the script that Spielberg would eventually take over.

After Kubrick's death, Spielberg decided that he would make A.I. his next project in order to honor his good friend. He set out to find the perfect David. Of course, he didn't have to look very hard, because Haley Joel Osment was the most profitable child actor in the world at that time. He was also quite talented, and had already shown an amazing ability to take on a serious role without a hint of youthful irony or sentiment. Just what the doctor ordered.

Photography began in early 2000, and teaser trailers and websites were already making their rounds. Finally, people were saying, Spielberg is making another whimsical fairy tale for children. He's making an E.T. for the new generation! It's even got an acronym title! The problem with this theory is that the movie is about death, disappointment, and the hatred and selfishness that lies inside all of us. The movie is about loss and pain. It's about companionship, and how some things were made to be broken.

This is powerful (and, admittedly, kind of emo) stuff for a kid's film. I guess that's why it isn't a kid's film. It just has kids in it. You know, like KIDS. So, to everybody's surprise, A.I. turned out to be a rather nihilistic portrait of America gone wrong, and parents everywhere swore to never trust a trailer with whimsical guitar ever again. Look at that logo. The boy is looking up, as if there's hope.

But this isn't Spartacus or Paths of Glory we're talking about here. This is late Kubrick. This is Eyes Wide Shut Kubrick. He has seen the joy and love that people share. He's here to show us why that's so important. He's here to show us what happens when that goes away.

A.I. tells the story of a mother, Monica, whose son is dying of a rare disease with no cure. Every morning, she goes to the boy's cryogenically frozen body and reads books to it. She spends her days folding and washing his clothes. Wishing he were around.

One day, her husband comes home with a surprise. There's a new kind of robot, a boy robot, that has a software that enables him to love. All she has to do is activate the software, and the immortal robot boy will love her, unconditionally, forever. Monica is outraged by the very thought of replacing her son. Besides, the robot, named David, will never feel genuine. What good is love if you've had it programmed? But what is motherhood anyway, if not a love you yourself have created?

Before long, Monica decides she'll accept the offer. She programs David to love her, and he is immediately obsessed with his mother. He follows her all around the house. He helps her with her chores. He gives her constant care and validation. Monica is appropriately freaked out.

What is so fascinating about this movie is the way that it understands love. In the film, love is not companionship or respect or trust. It is obsession. David is obsessed with his mother. Everything he does is somehow a reflection of his obsession with her. For David, love is a disease. And there's no cure.

And just when Monica was starting to come around to the idea of loving David back, her son is miraculously cured and sent home. This shatters David's world. Why would Monica love David, her replacement son, when she's got the real son all to herself? Besides, he's a real person who can grow old, reproduce, and eventually die. He is not immortal. He is not a constant reminder that one day all of us will die.

This is really heavy stuff for Spielberg, who even ended his Holocaust movie with a triumphant rescue scene. In A.I., we have to watch a child's (albeit a synthetic child) arbitrary quest to find a way to become a real boy so that his mother can love him.

After a few misunderstandings, David is abandoned in the woods by Monica, where he meets a fugitive robot who was designed as a male prostitute. From this point on, the two robots go on a mission to find the Blue Fairy (as seen in a Pinnochio picture-book his mother so indiscreetly read to him), and, by extension, a way for his mother to love him again.

We know the entire time that David's journey is ridiculous. There is no blue fairy. It is impossible for him to become a real boy. And as we see him travel further and further into this dystopian America, the more we realize that the human race is completely falling apart. Robots live forever. Their energy sources never die. And, as Jude Law's Gigolo Joe tells David, "When the dust settles and the fire goes out, all that will be left is us. And they hate us for it."

Entire game shows are dedicated to the destruction of robots. This is not because humans hate robots, but because they fear their own mortality. People get older. People die. These robots aren't natural because they don't age. They don't change. They are forever. This isn't a story about a robot becoming a real boy, but of a robot coming to terms with the mortality of those around him. He has to learn to accept that death is natural, and that he is not of the natural world.

SPOILERS AHEAD

And this is why the ending is so necessary. The theme of the movie is that we can't stop death. That everything must, one day, come to an end. When David is stuck in front of the Blue Fairy statue, what we see is a young boy who is still full of hope. He still believes in magic. He is still a child. However, 2,000 years later, David is unearthed by highly advanced robots (yes, those are robots--they have digital faces, and they have lived longer than humans, just as Gigolo Joe predicted they would), he is given the chance to spend one more day with Monica.

When I first saw the film, I was very upset with this ending. Why wouldn't they end it with a shot of the Blue Fairy, wooden and inanimate at the bottom of the ocean? It fit better with the hopelessness of the film. I thought, jeeze Spielberg, way to schmalz it up for us. But now, I see this as a much more horrifying conclusion. He does not get to spend the rest of his days with Monica. No. He gets to spend one day with her. And he can live forever.

So what do they do? He makes her coffee and they read together. And then she goes to sleep. That's when she dies. David will wake up next to Monica, who is dead, and he'll spend the rest of eternity with faceless robots that only care about using David like he's a museum artifact. The robots are merely replacing the humans in his situation. He is still being objectified by the very beings that allow him to live. He was created to fulfill a curiosity. He was built as a substitute for grieving parents to cope with. Now he's a substitute for the entire human race, which ceases to exist at this point in the future.

A.I. is a daring, high-budget concept film that analyzes the darkest depths of the human soul. It shows us death and suffering and fear, and it does this through the lens of a beautiful retelling of Pinnochio, only, without that happy ending where he becomes a real boy. It's not a perfect film. There are pacing issues and sometimes it's a little too on-the-nose with its message, but I greatly admire Spielberg's work, here. This is some of the most interesting material he has ever worked with, and probably the last movie he'll ever take a real risk with, considering the reviews and box office returns.

If you saw this movie years ago and didn't like it. Try it out again. If anything, it's a bizarre relic of Hollywood squeezing out a sad, nihilistic movie about death marketed for children.

I give A.I. Artificial Intelligence an 8 out of 10 annoying Clockwork Orange fans.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

The Essentials, Part 4: Comedy

|

| Tati's social commentary tickles my funny bones all over! |

Humor isn't objective. All of these lists, these essentials lists, are just guides that are totally opinion-based. This is your road map to my favorite films of all time, and my reason for writing it is just so I can share my thoughts with you in the hopes that you'll do the same. I want to hear what films move you, and what films have shaped you as a person. Also, I am mostly trying to fill these lists with films you don't ordinarily come into contact with. So, of course, I also love Ghostbusters, Airplane!, Zoolander, etc.

Here are some comedies that have shaped me. For better or for worse.

Playtime (1967)

Jacques Tati's Playtime might be the most ambitious comedy ever made. He built an entire city, hired thousands of extras, and went completely bankrupt trying to get this movie produced. It is a sprawling, three hour epic that is told almost completely without dialogue, and the huge set pieces are so overwhelming that you have to see the movie twice just to see all of it.

Playtime was shot on 70mm film, and it was screened on giant, IMAX-like screens for French audiences who had pretty much stopped paying attention to Tati's Mr. Hulot series. It took three years to film, and it is one of the most visually arresting movies of all time, with some of the greatest set designs you'll ever see. Three hours sounds like a hard sell for a near-silent comedy, but please give this one a try. It is one of the great cinema masterpieces.

Love and Death (1975)

What more is there to say about Woody Allen? The man has had a huge impact on my life, from my sense of humor to my outlook on life and people and humanity. He releases a new movie each year, and each year we talk about whether or not it's as good as his "earlier, funnier"movies. And while I think that his '80s period is his most ambitious and interesting decade, I will say that the most enjoyable stuff that he produced, just on a laugh-a-minute scale, is his early '70's screwball comedies.

And no other Woody Allen movie is as funny, and sophisticatedly ridiculous, as his Love and Death. It tackles everything from Russian Literature to empty marriages, from Socrates to Ingmar Bergman. It comes at you with a new joke ever couple of seconds, and nearly all of them work. This is the film that puts Woody Allen up there with the best humorists of all time.

The King of Comedy (1983)

Martin Scorsese's oft-overlooked masterpiece is also one of the director's most poignant efforts. Robert De Niro plays the part of Rupert Pupkin, a bad stand-up comedian who will do anything to appear on a late night talk-show to perform his act and get the fame he so rightly deserves.

When the host, played by Jerry Lewis, says no to his act, Pupkin decides that he'll just kidnap the man and hold him for ransom until he's allowed on the show. The movie is dark, disturbing, and strangely prophetic of current attention-seekers. Check it out.

Noises Off (1992)

Michael Caine, Carol Burnett, Christopher Reeve, and John Ritter headline this hilarious farce directed by Peter Bogdonavich. This film is actually based on a play, and the play is insanely impressive, but this movie's cast is so remarkable that you can't say no to watching this movie.

The basic story is that Michael Caine is a theater director who cannot get his actors to stay happy during a particularly problematic stage production. This is some of the most clever writing I've seen, and the timing is impeccable. Pick up this movie. Watch it right now. It is amazing. Also, a shout out must be made for Bogdonavich's other farce, What's Up, Doc?, which is also quite hilarious.

Coffee & Cigarettes (2003)

I like my comedies with a dash of melancholy, and I could have really chosen any of Jim Jarmusch's films for this list. His humor is as deadpan as it gets, and sometimes it's hard to tell if what you're seeing is even supposed to be funny. That's the way I like it. But Coffee & Cigarettes might be his purest expression of straight comedy he has ever released.

The highlights include segments that center on Steven Wright, Alfred Molina & Steve Coogan, and Bill Murray & the Wu-Tang Clan. Most of the film is divided up and available on youtube, and I highly suggest you seek it out. Some of the funniest stuff I've ever seen. The Tom Waits & Iggy Pop bit is irresistible.

In Bruges (2008)

I'm not kidding. I love my comedies with a side of melancholy. Otherwise, how do you know when to laugh? There has to be a contrast of some sort for the comedy to work at all. And with In Bruges, the very setting is the straight man. If you haven't seen this movie yet you are doing everybody a disservice.

What are you even doing here? Get out. Get off my blog and watch the movie.

What are some of your favorite comedies?

Honorable mentions: Network, Broadway Danny Rose, Galaxy Quest (yes, seriously), Harold and Maude, Being There, Happiness

Saturday, July 14, 2012

Movie Review: Moonrise Kingdom

I've had several conversations recently regarding Tom Cruise. "He's the same in every movie," the other person says. "He's always Tom Cruise." Usually they cite a couple of his characters from different decades and smile at me: the argument, for me, is futile. And perhaps they're right. But I don't really believe in the every-good-actor-disappears-into-a-role thing. I believe in the theory of characters and stars, and Tom Cruise, obviously, is a star.

Let me explain-- since the beginning of cinema, movie studios have invested huge amounts of money into recognizable stars for their films. The star was the connection between good movies, and people often made (and continue to make) their decisions based on what they already knew about the film going in. Oh, Buster Keaton is funny, let's go see the new funny Buster Keaton movie. Oh, Cary Grant is handsome and charming, let's go see the new romantic Cary Grant movie. And so on.

These early stars weren't even allowed to disappear into their roles because these clearly defined roles were necessary for the film's income. Flash forward a few decades. The star-power theory is relatively unscathed. Sure, there are films starring unknowns that do well in the box office, but that is almost always because of genre-power or director-power, subsidiaries of the star-power theory. Paranormal Activity might not have any stars in it, or a popular director, but horror films are their own stars-- people go in expecting the formula to deliver.

So when people tell me that Tom Cruise is the same in every movie, I usually vehemently agree. The problem with disagreeing is that I don't have very many roles to choose from to support my stance. Sure, there's Tropic Thunder and Magnolia, but these are only small attempts by Cruise in becoming a different kind of actor. Maybe, in another world, he could have been. But he isn't. He's a star.

|

| I thought this was a Moonrise Kingdom review? |

There are two kinds of actors, the star and the character. We're all familiar with these terms. The star has his/her name above the title of the film. We go into the movie expecting what we've seen of this person, and if we're lucky, they will deliver the goods. For example, I love Will Smith movies. I can't help it. I find Will Smith to be effortlessly, brilliantly charming. Even in a bad movie, I will always like Will Smith. However, with only one or two exceptions (just like Cruise), Will Smith is always the same person. Always. George Clooney is the same way. As is Emma Stone (shock!).

Calling a star a star is not an insult to me. It's just calling it as it is. The people I just mentioned are excellent at being stars. These are people who appear in several movies of various time periods, tones, and intents, and always come out of the other side satisfying that desire in us to get more of our stars. Sometimes they play their roles a little straighter, or a little looser, but they're always instantly recognizable. And don't act like you don't love this. It's comfort. It's home. Why else do we desire to see them again and again?

The character is a whole different kind of animal. These are people who thrive on audiences not knowing their names. Plenty of stars have transitioned from being characters, but very, very few stars have transitioned into characters (see: Tropic Thunder). This is because stars have more at stake. They have empires built around their product. Characters do not. They often play small, but important, roles in big movies, and large, significant roles in small movies. These are people like Dylan Baker, Harry Dean Stanton, and Gary Oldman. These are people who make their living in becoming other people. They are there to help create the believable world for our star, whether that star be a genre, an actor, a writer, a director, or a franchise.

|

| This is where I talk about the movie--kind of |

This is because people have lumped Wes Anderson into the same category as Tom Cruise. They say he's always the same, and is incapable of surprise. Even Anderson's stop-motion kid's film (his Tropic Thunder) has the hallmarks of his live-action counterparts. Does this mean that Anderson is lazy, or does this mean that Anderson is fulfilling the desires of his fans? Does he have any real reason to change? His movies do well critically and commercially (commercially not as much, but the films make money) and he has placed himself firmly into a niche from which he'll probably never want for anything.

Anderson's detractors want him to be more like Michael Winterbottom-- eclectic and versatile and impossible to recognize. But Anderson can't be Michael Winterbottom; people already know who he is. He has already become a star, and stars have a hard time disappearing.

|

| Okay, Okay. The actual review |

I'll confess that I wasn't all that excited about Moonrise Kingdom when I first heard about it. This is odd to me, because in my teens I was all about Wes Anderson. I particularly loved The Life Aquatic, which was, to me, one of the most interesting character studies I'd ever seen. And one of the most beautifully shot and art directed, to boot. I also loved The Darjeeling Limited for its slower, more serious delivery. It was Wes Anderson moving in a different speed, and I liked it. I saw both movies opening day and loved every second of them. I saw both movies multiple times in the theater, with different groups of people, and watched their reactions. To me, everybody was thinking "who is this guy making these weird little movies, and who is giving him the money to build those sets?"

I heard the same thing last night, watching Moonrise Kingdom, in my own head. I asked myself around the halfway mark how this movie got made. The sets are spectacularly realized. Real money was spent on the look of this movie, and I couldn't, at first, wrap my head around it. And then I remembered that Bruce Willis, Bill Murray, Frances McDormand, Edward Norton, Harvey Keitel, Jason Schwartzman, and Tilda Swinton star in this film. I'm sure they had something to do with it. But then another voice asked me, in a much more confused tone, why is Bruce Willis in this movie? Bruce Willis is a star. He doesn't need to be a supporting player in a limited release film starring unknown child actors. But then I thought, yes, this is his Tropic Thunder. This is Bruce Willis holding on to the character actor buried inside of him, as he often does every few years, and in this case the gamble paid off. Bruce Willis is the heart of Moonrise Kingdom.

At the start of the movie, I realized two things: it is filmed in an aspect ratio Anderson hasn't used since Bottle Rocket, and he is using a different font for his opening titles. These changes may seem innocuous to those who are unfamiliar with the Tom Cruise Smile that is Anderson's visual style, but for those of you who follow the director, these are huge changes. Monumental, even. And I was listening once I realized these changes.

Moonrise Kingdom follows the plot of two twelve-year-olds, Sam and Suzy, as they run away and try to make a life for themselves in the wilderness using Sam's Khaki Scouts skills. The two quickly fall in love and seek a life of adventure as fugitives. We follow two stories, the story of the lovers and the story of the adults who look for them. And, in keeping with perfect Anderson tradition, the irony here is that the adults act like children and the children act like adults. We get a very real love story between the leads, acted and blocked like a classic Jean Luc-Godard film (using a tripod), and the scenes are filled with warmth and unusually deep emotion. We also get a very real search-and-rescue story, complete with split-screen phone calls and perilous cliff-side chases.

However, those looking for a truly different Wes Anderson movie will have to look elsewhere. His star power shines so brightly in every shot of this film that detractors might as well call it a parody. We have extravagantly designed sets, cameos from all the major players (excluding the Wilson brothers), the use of correspondence stock, a fantastic, eclectic soundtrack, warm, autumnal colors, and deadpan delivery of every funny line of dialogue. We get the classic Anderson conversations beats, such as "Aren't you concerned that your daughter is missing?"

"That's a loaded question."

Those of you who are on the fence about Anderson's movies might not find much to be surprised by in his new film, but I will say that Moonrise Kingdom is much more fun than I anticipated, especially in its unusually cartoony third act, where any hint of realism is completely thrown out the window. I found Anderson's total departure from realism charming, and the finale helped me get on board with the movie. I also can't say enough good things about Edward Norton and Bruce Willis. Norton has the gee-whiz attitude necessary to make his character believable as an innocent and excited scout leader, and Bruce Willis has the world-weary exhaustion necessary to make him believable as a bored, depressed police officer stuck on an island with no easy exits.

Bob Balaban also offers an interesting performance as the film's narrator, who guides the movie like he's part of Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom, and I found his costume to be one of the highlights.

It's hard for me to judge a star for using his gifts. I often find myself defending them vehemently at social gatherings, and sometimes I get exhausted at the very mention of Nicolas Cage or Tom Cruise. So when somebody mentions Wes Anderson, and another person inevitably sighs and says he keeps making the same movie, I sigh too. It's true, Anderson seems to be stuck, maybe even obsessed, with a very particular style of filmmaking and a very particular story, but let's stop expecting him to change. For me, he is good at what he does, and if you don't like it, you're not wrong or stupid or out of the loop, you're just not a fan of this particular star. It's okay. There's an infinite number of stars.

I give Moonrise Kingdom 8/10 vacant, deadpan stares into the camera.

Monday, July 9, 2012

Hint Reviews (Movie reviews in 25 words or fewer)

Pixar tries its hand at making a Dreamworks movie, and it succeeds. Beauty and artistry mixed with well-worn plotting.

Mark Wahlberg proves yet again that he's one of the funniest men in Hollywood; Seth Macfarlane proves he can write without tangents.

Not even a silly lizard can get in the way of this unnecessary, yet unnecessarily good, reboot of the popular comic. Garfield and Stone shine.

McConaughey gives the performance of his career in Soderbergh's under-written and over-directed crowd pleaser.

Excellent performances and direction try, but ultimately fail, to make Prometheus anything more than an okay Sci-Fi tentpole. Charlize Theron's character is wasted.

Mark Ruffalo raises the bar for Hulks everywhere; Whedon reminds us that superheroes are supposed to be fun.

Kristen Stewart falls victim, yet again, to lousy writing and poor direction. Nice visuals don't make up for another wasted Charize.

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Why Breaking Bad is My Great American Novel

|

| What season is this from? |

People keep talking about this Great American Novel thing, and they keep asking if there will be "another" one. It's a valid question, I suppose, as most people assume that the goal of any American writer is to write the Great American Novel, be endorsed by Oprah, and then have a movie adaptation made of his/her great work.

Some people might say that Jonathan Franzen has come the closest to writing a modern Great American Novel, but of course, we all know that the very existence of such a thing is preposterous. There is no Great American Novel, and if there were, nobody would want to read it. Look at Ulysses, one of the most widely beloved novels of all time, and then try to find ten people you know who have read it and enjoyed it. Something of such monolithic artistry and beauty cannot be lowest common denominator. Nothing can be universally beloved, especially by a country as diverse and divided as this one.

Heck, there are even some people who don't like Ryan Gosling, even if they only amount to an army of six. But if you're going to be a "reader," you have to play the game.

Because, as we all know, people aren't actually asking about the Great American Novel. They're asking about the Good American Novel, which is something else entirely. The Good American Novel can be anything, really. For some people, that novel could be written by James Patterson. For others, that novel could be written by Danielewski.

However, if people ever ask me what the modern Great American Novel is, I'm usually divided between two brilliant, collasal works of genius: Breaking Bad and Mad Men. I'm not being cheeky, either. These are seriously, in my opinion, the greatest works of American fiction in the modern era. Like Dickens before them, Matthew Weiner and Vince Gilligan are using serial narratives to weave portraits of modern-day existence. And I'm using modern loosely here, as we all know that Mad Men takes place in the past. But, of course, it is also extremely modern in its storytelling--especially in its most recent season.

But nobody is satisfied with two answers to that question. They want the definitive greatness of one answer. So, I will give you a definitive answer, and my answer is that Breaking Bad is the best piece of modern American fiction.

|

| What season is THIS from? |

In Mad Men, everybody is slowly turning into his/her mentor. Peggy is turning into Don, Don is turning into Sterling, etc, and part of my fascination with the show is watching the surprising, sometimes unsettling ways in which the characters parallel and play off of one another.

In Breaking Bad, one might argue that Walt is also turning into his mentor/nemesis, Gus, but I would be quick to point out that almost everything Walt does is characteristically anti-Gus. Everything Walt strives to be is placed right in front of us in the fifth episode of the series. He shaves his head, puts on some sunglasses, and finds a fedora. He becomes Heisenberg--the coldhearted meth cook who doesn't mess around with idiots. Of course, the constant problem with Heisenberg is that he doesn't exist. He is merely Walter White in disguise, and Walter White is just a sad, arrogant, pathetic human being looking for success.

Don Draper, on the other hand, has success. He has a ton of success. He may have hit rock bottom in season four, drinking so hard that he loses days at a time, but his rock bottom is still upper class and comfortable. He still finds ways to succeed because he is a machine of success. The great flaw of Don Draper is that he has succeeded so much, and so often, that he cannot handle a life without constant affirmation.

Walter White is the exact opposite. He thrives in situations where there is no hope for him. However, any amount of success drains Heisenberg of his supernatural gift for level-headed and brainy solutions. Success is Walt's kryptonite, whereas Don's weakness is his inability to cope with a world filled with people who aren't as amazingly competent as he is. Don's protege is Peggy because she is also a machine of success who has no patience for the Walter Whites of the world.

Walt's sidekick, Jesse Pinkman, is similar to Walt in more interesting ways. First off, it is technically Walt who is Jesse's protege, as Walt spends much of the first season learning how to be a criminal from Jesse. Their relationship works both ways, as Walt, the chemistry genius, has absolutely no concept of how the drug trade works, and vice versa. As Peggy spends much of Mad Men building her confidence and honing her craft, Don spends the majority of the series treating her like she should never be proud of herself. Don seems to go out of his way to act like he has never learned anything from her. His career, as far as I see it, would be the same with or without Peggy.

Walt, without Jesse, would be nothing. He would have died in the first season, by Tuco's hands, in the middle of a junkyard (not a mall), and Walt knows this. He needs Jesse, as he repeats time and again to his various bosses, because they have a true partnership. When Walt is in trouble, Jesse sticks his neck out. When Peggy is in trouble, Don leaves her out to fend for herself and maybe learn a thing or two.

And it's not that I mind Don treating Peggy the way he does, but I do mind that this seems to never change. With Walt and Jesse, their relationship is a roller coaster. In one episode, they are literally risking their own lives to save the other's, but in other episodes they are each other's worst enemies. The problem with Don and Peggy is that Peggy is the only dynamic character in this relationship. The Peggy we see in the pilot episode is very, very different from the one we see in the final episode of season 5, sitting in her hotel room smoking a Virginia Slim. The Don we see in that very same episode is absolutely no different from the one we see in the pilot. Of course, this is part of the tragedy of the fifth season finale, but it is also something that alarms me about the series. It is not taking any true risks with the character of Don. Just when we thought he would break from his pattern and really become a dynamic character, he shifted back to his normal self. Yes, it is an American tragedy, but it is also not very rewarding to the audience.

On the other hand, Walt is the most dynamic television character I have ever seen. He is slowly transforming into the antagonist of the show, and with each episode, a little bit more of our sympathy moves from Walt to the people he is hurting. He is fundamentally changing throughout the show, until finally the audience realizes that Walt has become a sociopathic maniac who holds none of the values that got him into the drug trade in the first place.

The status quo of Breaking Bad is to never have one. The stakes are different in each episode, and huge character and setting changes take place so often that it is easy to forget where we've come from. The pilot episode is almost unrecognizable when compared to the final episode of the fourth season, as so many monumental twists have taken place.

The tragedy of Walt is more significant because it is one based on greed, destruction, arrogance, and false values. Walt is doing all of this for his family, as he says, but we can quickly surmise in later seasons that Walt is willing to sacrifice everything in order to be respected by his new peers. Walt is a failed chemist who has spent the last few years in a high school classroom, and he wants his last days on Earth spent becoming the best in the world at something. He strives for the success that he so narrowly missed out on decades ago. His rise to power mirrors that of America's, and his lust for domination is the most destructive force in the show.

Don and Walt both live double lives, but Walt's is more immediate. Don is a deserter and a liar. His true identity is concealed by years of deception, but the Don that walks the halls of Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce is the same one that goes home at night to Megan. Walt, on the other hand, deals with Heisenberg on a daily basis, and even when he does finally come clean to Skylar about his secret life, he never fully confesses. Walt and Heisenberg can never truly be reconciled because they are oil and water. Heisenberg is the monster that lives within Walt, and Walt is too greedy to stop him.

Breaking Bad is on a huge scale, morally, politically, and artistically. The show excels on a dizzying number of levels, and when compared to Mad Men's slow-burn, perfectly choreographed pacing, it feels like a nuclear explosion. Mad Men might be the classiest, most beautifully shot piece of television ever produced, but Breaking Bad's kinetic, perfectly acted and scripted episodes are, in my opinion, turning into the Great American Novel.

EPISODES OF NOTE

SSN 1 EP 6 Crazy Handful of Nothin'

SSN 2 EP 6 Peekaboo

SSN 2 EP 13 ABQ

SSN 3 EP 7 One Minute

SSN 3 EP 9 Kafkaesque

SSN 3 EP 12 Half Measure

SSN 4 EP 1 Box Cutter

SSN 4 EP 10 Salud

SSN 4 EP 11 Crawl Space

Monday, May 28, 2012

Movie Review: Men in Black 3

What has changed since 1997? Certainly the scope of what computer effects are able to accomplish has shifted. We've grown accustomed to the things that used to wow us. For instance, that final reveal at the end of Men in Black where the galaxy is all part of a game of marbles was immensely awe-inspiring when I saw that film in the theater. Today, that scene would not be enough to wow me. We've grown jaded, and this is not good for Men in Black.

The first film put a lot of stock in special effects wizardry and make-up. It is one of the rare occasions where a big-budget blockbuster's special effects were used to make jokes even funnier. It is, in my opinion, the first film to truly integrate computer effects in a way that served the film and made it better. And yes, I've seen Forrest Gump.

Men in Black had a huge effect on me when I was younger. I was introduced to a world that was very similar to my own, yet it contained all of the nightmares and dreams that, at the age of seven, only I could see. I loved that aliens were real and living amongst us. I loved the idea of a disguise, of a secret agent, and of having gadgets that accomplish impossible, amazing things. The film played with the importance of size. The "midget cricket" serves as an excellent taste of foreshadowing, and is one of many clever, inventive storytelling devices used in the film.

Will Smith's Agent J truly goes through a narrative arc in the film--beginning his story as a cocky and world-weary NYPD officer and ending the film as a man who knows there's always mystery left in the universe. He grows to truly care about his partner and the planet that he is saving. Tommy Lee Jones's Agent K is a delightful play on the classic Jones character, looking stone-faced into the absurd and asking it to follow arbitrary rules. He, too, follows a satisfying arc where he grows from being a jaded intergalactic detective to a happy, blissfully ignorant retiree. Men in Black is one of those great Hollywood blockbusters that just works. The chemistry between the actors, the visual effects, the world-building, and the story structure just seem to effortlessly click.

So what went wrong with Men in Black II?

Well, this poster sums up a lot of it. Look at Agents K and J sitting in those chairs and holding those guns. Those chairs are featured in a famous recruiting scene from the first film. The guns are featured from the finale of the first film. Neither of those things appear in the second film. However, approximately everything else does. The second film seems to exist for the sole purpose of retreating the first film. The coffee-pouring insects that worked so well as an element of world-building? Lets cast them as crucial, plot-progressing characters. The dog with a couple of lines that serves as comic relief during the most tense section of the first film? Lets improbably make him an agent and make him spout out hundreds of desperate attempts at catchphrases.

Also, the first film had a fantastic, disgusting villain in Vincent D'Onofrio's cockroach. He was gross, manic, mean, offensive, and exactly the kind of villain these guys would have to fight on a weekly basis. He was a roach, he was vermin, and he wanted revenge on a planet that treated his family like scum. His motive is built into the audience's everyday life. It's a brilliant conceit. Lara Flynn Boyle's sexy plant-vine villain is...less brilliant. First of all, her minion is the instantly dated joke of Johnny Knoxville acting, and second of all, she's a lingerie model who doesn't seem to have any other motive that just being evil.

The second film is sloppy. It resurrects Agent K because it needs to, it uses a sexy villain because marketing executives asked it to, it overindulges itself on previously used side-characters because it didn't trust the creative team to create new ones, and it seems to only exist because somebody out there liked the talking dog.

So why even bother with Men in Black 3? If the second film was already desperately clinging onto its franchise roots for inspiration, how must the third film fare?

Well, surprisingly, it's actually pretty good.

What the third film carries with it is the wisdom gained from the dreadful sequel. Gone are the petty references to the first film. Gone is a distractingly over-sexualized villain (unless you find the man in the above picture hunky), and gone is all of the sloppy plotting that comes with bringing back an essentially killed-off character. Which is funny, because this film's plot is bringing back a killed-off character.

I'll make it short, Jemaine Clement's hilariously cocky Boris The Animal escapes from Lunar Max prison and goes back in time. In 1969, Boris kills Agent K. Agent J, now a senior agent after 14 years of experience, is the only person who remembers Agent K from the present, so he too goes back in time to stop Boris from killing K. It's not a particularly creative premise, but the execution is fantastic.

Before I go into the performances and the excellent plotting, I have to point out the time-travel scene in which Will Smith's Agent J jumps off the Chrysler building. It is one of the greatest, most imaginative special effects shots I've seen in quite some time. See the movie just for that shot alone.

Anyway, Agent J makes it back to the sixties and the usual time-travel hilarity ensues. Andy Warhol is a bored, undercover MiB agent! Cops are racist! The Rolling Stones aren't old! I thought, for a few minutes into the sequence, that the film was going to roll over and just deliver cheap gags based around the time-travel conceit. But I was wrong. In fact, the film does very little in the form of cheap gags. When it tips its hat to the original film, it does so with background action. We see the site of the finale of the end of the first film deep in the background during a chase sequence, for instance. Nothing too forthright, nothing distracting. The film is just focused on the story it is telling, and it is focused on the characters who must make their arcs.

Replacing Tommy Lee Jones this time around (Jones is in the film, but he probably only worked for a weekend) is Josh Brolin, who does an absolutely remarkable impression of Tommy Lee Jones. It almost transcends imitation and turns into downright brilliance. Brolin disappears into the role and adds an all new dimension to the character of Agent K. I was shocked by Brolin's performance, and it gave the film a whole new weight that I haven't seen in the other two films. Also joining the cast is a character named Griff who can see every possible future and past of any particular scenario. He is played with awe-shucks sincerity by A Serious Man's Michael Stuhlbarg. Griff too adds to the emotional spectrum of the film. He adds the whimsy that was absent in Men in Black II because Agent J was no longer new to the club.

I hesitate to give you any more information than this, for fear I'll spoil some of the last act, which is a magnificently constructed set-piece that ends on an uncharacteristically emotional note for the series.

Was Men in Black 3 necessary? Not really, but it certainly works much better as a direct sequel to the first film than the second, as if the filmmakers too are embarrassed by that half-hearted entry. This film is funny, engaging, and surprisingly poignant. If you didn't like the first film, this one won't convert you, but if you too were disappointed by the second film's sloppy handling of the characters, then I think you should check this one out. It is an excellent way to spend your afternoon.

I give Men in Black 3 7.5/10 grumpy Josh Brolins

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

The Essentials, Part 3: The Strange

I've been asked over and over again what I find to be the strangest and darkest movies I've ever seen. Even though these sorts of lists will always be subjective, I find it even more subjective to list the weirdest movies I've ever seen. I mean, what I find strange could be something you find totally normal, and vice versa. So instead of just picking out movies that I find weird, I'm going to pull out, as I have before, films that I think used their bucking of trends and formulas to their advantages. These are the films that I would teach a class based around experimentation and a willingness to convey images and ideas not often associated with "the mainstream." In other words, this is probably the closest we're going to get to a list of my truly favorite films.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali's famously bewildering 1929 short film relied heavily on Freudian free-association for its screenwriting and also relied on nightmarish images for its shoot. The film is probably most famous for its eye-slitting scene (pictured above), but I admire this film for going out of its way to freak out its audience. I would even go so far as to call this the first truly successful horror film of all time. Perhaps I am cheating by including this film, seeing as its a short and all, but I really can't think of a better way to introduce experimental and surrealist filmmaking without subjecting a class full of students to Buñuel's madness.

Freaks (1932)

Tod Browning's infamous 1932 film put actual circus "freaks" front and center in the cast. This film came out before the Hollywood morality code, and because of this you'll see much more disturbing imagery and ideas in this film than any Hollywood film made in the 1940's or 1950's. Upon its release, Freaks some serious controversy for its unusual subject matter and frank depictions of deformity and human suffering. And, for 1932, this was an astoundingly bleak and original vision. Over the years, Freaks has achieved a strong cult following for both its subject matter and for the novelty of the time in which it was made.

Cat People (1942)

Jacques Tourneur made Cat People because he was fascinated by America's fear of female sexuality. The film focuses on Irena, a woman who is terrified by her own animalistic desires. Animals constantly call out to her. Sometimes she blacks out and has no idea where she was. She is afraid to sleep with her husband because of what might happen. Before long, Irena is transforming into a wild animal and killing whatever gets in her way. She cannot control her body or her thoughts. Tourneur's film is not only a landmark horror film with its willingness to let the true scares happen offscreen, but it is also perfect for a college class with all of its (for its time) progessive themes and ideas.

Pickup on South Street (1953)

Many mid-twentieth century cult films play with the subject of human sexuality in obscure and interesting ways. Pickup uses the imagery of a pickpocket on the prowl as a symbol for men who steal women's hearts. It's not a subtle bit of artistry, but the film uses this motif in interesting ways. Skip, the pickpocket, steals Candy's wallet -- a wallet which just happens to hold important communist information--and begins a complicated game of cat and mouse. This is one of Sam Fuller's Noir exercises, and he uses the genre's German Expressionistic roots to his advantage. A simple espionage film turns into a statement about human sexuality and sexual politics in the 1950's.

8½ (1963)

Fellini's films are often surreal, but few of them are able to implement their surrealist elements as organically as this film. A filmmaker struggles with the weight of expectation as he tries to film a movie that he has not yet written. He is surrounded by critics, reporters, and fans who all want to be a part of his newest masterpiece, but he has no idea how the movie will end. Fellini's film is a huge influence for the Cate Blanchett section of Todd Haynes's I'm Not There, and for good reason--this film is one of the great, uncompromising works of fiction that describes just how hard it is to live the life of the artist.

Persona (1966)

Persona not only plays with ideas surrounding identity and fame and mental illness, but the film itself is unusual in the way it was written, shot, and edited. The film concerns a mentally ill movie star who moves to a secluded island with a nurse. Most of the first half of the movie is a monologue from the nurse, who is trying to cut the silence left by the movie star with stories of her past. However, at the halfway point, the film switches focus. The film literally breaks, the identities switch, and confusion ensues. This film was a huge influence on the production of Robert Altman's 3 Women and David Lynch's Mulholland Drive.

Brazil (1985)

This film has nothing to do with Brazil, unless you count its soundtrack. Terry Gilliam's strange, surreal, and hilarious take on the future is one of the most unique film experiences that you can find. It is George Orwell seen through the lens of Franz Kafka. It is the nightmare of bureaucracy reaching its logical conclusion. The film concerns a case of mistaken identity that gets very, very out of hand. Gilliam's effects work mixed with his amazing ability to turn everything into a strange, dreamlike moment of surreality makes Brazil his crowning achievement.

Waking Life (2001)

Richard Linklater has made his fair share conversation movies. These films are usually just focused on listening to people talk about interesting and strange things they've seen in their lives. Slacker and Before Sunrise are probably his most famous conversation movies. However, I find Slacker kind of tedious and annoying because it seems to only have on perspective and that perspective is quite young. With Waking Life, Linklater has matured a little bit and decided to let in all sorts of points-of-view. The subjects discussed range from talk about dreams and death to talk about cell regeneration and governmental ethics. It's all over the map, and it meanders with its deliberate pacing. Fortunately, on top of the engaging conversations is a fascinating rotoscope animation that keeps the visuals of the film fresh and dynamic.

Inland Empire (2006)

If you've been keeping up with this blog for any amount of time, you'll know that I have a bit of a thing for David Lynch. And Inland Empire is, in my opinion, his greatest film. It is everything he has been working toward. He plays with identity, gender, fame, fiction, dreams, death, violence, betrayal, and love in this film with equal success. It is strange, scary, funny, and spellbinding. I believe there is no other film that could end a course on "weird" movies. This is the culmination of all the experiments that came before it.

What did I miss? What are some of your "strangest" films?

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

The Essentials, Part 2: Screenwriting

Since I'm trying to come up with a comprehensive list for beginning film studies students, I've decided that there will be no repeats on this list. If you think something from the classics list should be in this list, yet you don't see it, that's because you've already been told to watch it. I will be doing a full list of foreign films in the future, and so I am going to try to keep them at a minimum until I devote a post solely to them.

For this list on screenwriting, I am going to focus on films where the writing is not only strong, but it is also successful in conveying the kinds of things you learn in a screenwriting course, such as character development, plotting, pacing, dialogue, moral and social issues, etc.

City Lights (1931)

Just because there's no spoken dialogue, that doesn't mean a film didn't have a writer. Chaplin's City Lights is a beautiful, heartbreaking love story acting like a simple mistaken-identity comedy. The complexity of its writing sneaks up on you in the third act, when the poor tramp is finally recognized by the blind girl selling flowers on the side of the road. When she realizes the kind of sacrifice the tramp has really made, it's hard to keep your eyes dry. This is one of the best, and earliest, examples of the set-up/pay-off screenplay formula. Almost everything that happens in the first half of the movie is referenced again in the latter half, and Chaplin's tight pacing and structure makes this one of his most watchable films.

M (1931)

M deals with moral ambiguities that even most modern films won't touch. Here we have a man who has a compulsion, a sick compulsion, to murder children. He is terrified of his own desires, and with each murder he commits, the more insane with guilt and anger he becomes. We see a courtroom scene unlike any other, presided over by the criminal underworld, where the guilty judge the guilty, and the moral ambiguities of this scene are constantly observed and understood by the characters. This is a triumphant film because it investigates the darkness inside all of us and passes no judgment. It merely watches these people interact with one another, and it is a bold vision.

Double Indemnity (1944)

The frame narrative works in Double Indemnity because of the stylistic formula of the Noir. A dissociated voice, somewhere in the clouds, tells us what happens to the people we're watching with an unbelievable clarity. The voice knows where this story goes, he's seen it before, and we're just along for the ride. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler's script is one of those classic three-act screenplays that delivers exactly as the formula requests, but delivers so well that we forget how many times we've seen the story.

High Noon (1952)

Carl Foreman's screenplay for High Noon was written as a direct response to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Foreman was blacklisted in Hollywood as a communist, and this screenplay is his reaction to his persecution in the midst of the Cold War. Marshal Kane, played by Gary Cooper, is out against the world and there isn't anybody who can help him. The film takes place in real time, and we get a snapshot of Kane's existence, alone and scared and dark, and all of this is part of a bigger picture--the world, in 1952, was scared and desperate. Foreman writes from a place of fear, and Kane, cornered by the opposition, can do only what he knows how--kill.

The Graduate (1967)

Benjamin Braddock is a product of the fifties trying to make sense of the changing times. He's just graduated college and he's looking for a place in the world. He holds on to his youth, to his need for a maternal figure, to a person who has already found success and comfort. He knows he can't love her, but he does. It takes the youth of her daughter and the unknown future that she represents for Braddock to grow up. He breaks through his youthful need for a security blanket with his young love, but, in that final, brilliant shot, Braddock remembers that the future is unknown. Where is he going now? Buck Henry's script perfectly encapsulates that feeling of unease that surrounds a time of great change. His movie is the late 1960s.

Scenes from a Marriage (1973)

Scenes from a Marriage chronicles the slow disintegration of a marriage. It begins with the Marianne and Johan's friends announcing their divorce. Marianne says that'll never happen to her own marriage. Johan isn't so sure. This is the beginning of a decade-spanning conversation that covers the mountains and valleys of a long-term relationship. Bergman investigates marriage with an honesty that I've never seen before. These characters rip one another apart, but we are never exposed to melodrama or easy answers. There are no bad guys, just two people getting to know one another better than they know themselves.

Paris, Texas (1984)

Sam Shepard wasn't done with the screenplay when production started on the Palm D'or winning Paris, Texas. The story follows Travis, an amnesiac wanderer who is picked up by his brother and slowly comes to remember who he is and what he cherishes the most. The screenplay is about family and memory and love and anger and guilt and, in the end, nobody quite gets exactly what they want. This movie contains, what I think, is the best monologue ever written. Watch it.

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Do our past actions define us, or are we defined by our promises of the future? What is guilt if it isn't our conscience trying desperately to define us as unworthy? Woody Allen's masterpiece, Crimes and Misdemeanors, addresses the big questions. What is true justice? In a world of murder and rape and disgust, what is true evil? Aren't all living things evil by default? Is there a spectrum of the crimes that we commit, or does everything we do rattle with equal significance? This film deals with guilt and anger and despair in a more mature and honest way than I have seen in any other film. A truly powerful piece of filmmaking.

Breaking the Waves (1996)

Lars Von Trier has made a name for himself with his stories about women in dire circumstances. They often end tragically, and Breaking the Waves is no exception. However, unlike some of his later films, Breaking the Waves doesn't have some sort of film gimmick, like musical numbers or minimalist set design. No, this film is just pure story, pure writing, and it is devastating. Trier's recreation of the passion play is moving and tragic, but in its final moments, it is transcendent.

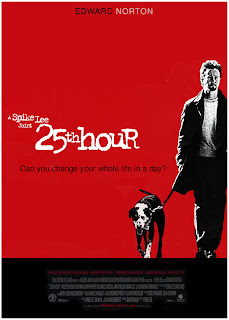

25th Hour (2002)

David Benioff's 25th Hour is about post-9/11 New York. Of course, the plot surrounds Monty Brogan as he lives his final day before going to prison for felony drug trafficking, but this story is really about how America deals with difficult times. Monty is angry and frustrated that his life has ended up the way that it has, but he is also responsible. He got greedy, he took things that didn't belong to him, he made decisions, big decisions, for other people. He embraces everybody of every color and creed, but he doesn't love them equally. In fact, he equally despises them. Monty has dreams and ambitions that he'll never be able to achieve because of his charred past. He blew it, he knows it, and he's trying to pick up the pieces.

What are some of your favorite screenplays?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

__BreakingTheWaves(1).jpg)