When I saw the emaciated, tired, dehydrated John Hawkes in last year's fantastic Winter's Bone, I knew that I'd quickly see him again in a role that truly let him inhabit what Bone only hinted at. He's got a spark in his eyes that requires attention, even sympathy. Even when the rest of him is angular and cold. He's got a mean face and a cracked voice. In Winter's Bone, all it takes is one long look for him to make his points. We can just look at his eyes and know what he's seen.

Sean Durkin, the writer and director of the haunting Martha Marcy May Marlene, must have seen what I saw in Hawkes last year. Only, instead of playing a guilty man trying to go clean, Hawkes has been cast as the charismatic leader of a small commune in the Catskill mountains.

Sadly, Hawkes' character, Patrick, has been relegated to a supporting role.

This is not to say that the film is ruined by this fact, but I am confident that a film about Patrick would be infinitely watchable. Hawkes gives the best performance in the movie, and one of the best performances of the year, and there is, somewhere deep down, a pain in my heart that he isn't given more screen time here to work with. But lucky for us, Elizabeth Olsen is also in the movie.

Playing the titular Martha (sometimes Marcy May, sometimes Marlene) is Olsen, giving a totally out-of-nowhere debut performance that somehow carries the enormous weight of Durkin's unusual and disturbing screenplay, jumping between the confused and emotionally exhausted Martha and the confident leader that is Marcy May. The chronology of the film is jumbled, not unlike 21 Grams or Pulp Fiction, and sometimes the audience is unsure of which timeline Martha is in until late in the scene.

Martha Marcy May Marlene centers around a young woman, Martha, who is accepted into a commune in the Catskills and is slowly brainwashed into believing the increasingly dangerous rules and philosophies professed by the commune's leader, a much older, enigmatic man named Patrick.

A parallel plot runs through the film in which Martha has run away from the commune and is taking shelter at her sister's lake house in Connecticut. Martha, in these lake house scenes, is tormented by her memories of the commune, where she took the name Marcy May and witnessed countless disturbing and horrifying actions by her "family."

The film seamlessly cuts between the two stories, linking them with visual motifs, music cues, and lines of dialogue. Before long, it becomes clear that Durkin wants to confuse us the way Martha is confused by her memories. "Do you ever wonder if something is a dream or a memory?" Martha asks her sister one night after a particularly haunting flashback. For the audience, we're thinking the same thing. These flashbacks are often followed by Martha waking up confused, scared, and looking for a way to escape.

The cinematography is elegant and fluid, much like the camerawork of Roger Deakins or Harris Savides, and the up-close, raw handheld moments in the otherwise perfectly framed shots punctuate the film with bursts of intensity. Durkin is a visualist who seems capable of creating the imagery we've seen from filmmakers like Andrew Dominik or Ingmar Bergman--ghostly visions that stay with us long after the lights have come back on. His ability as a writer may not be quite on par with his excellent eye, but his screenwriting chops are definitely there. The film's dialogue is mostly solid, but the real pleasure in Martha is its interesting use of story structure and juxtaposition. To give away the transitions and cues he uses would be a disservice to those of you who wish to see the movie for yourselves. So I'll just say this--the transitions are magic.

The highlights of the film are the great performances from Hawkes and Olsen, the beautiful cinematography, and the interesting structure Durkin has given the entire work. These highlights are definitely worth the price of admission.

What the film lacks is convincing motivations for the supporting characters, and what I think is a much-needed focus on the backstory between Martha and her sister's relationship. I could also do with more Patrick. Hawkes' performance is too good for us to get as few scenes with him as we do.

I give Martha Marcy May Marlene 7.5/10 confusing movie titles.

Hard opinions from a happy pessimist on movies from any era, any country, and any quality.

Friday, December 23, 2011

Sunday, December 11, 2011

Movie Review: Melancholia

It's another week, and it's another review of an apocalyptic film that deals with crippling mental disorders. However, unlike last week's Take Shelter, which had fun playing with our perceptions of what's real or what's imagined, Lars Von Trier's take is decidedly less subtle.

Melancholia is the second film in what I can only imagine to be the most devastating film trilogy of all time. Of course, Trier does not make trilogies in the literal sense, but he always works in threes stylistically and thematically. His most famous "trilogy" is the Golden Heart Trilogy, consisting of Breaking The Waves, his breakout masterpiece, The Idiots, his most unwatchable film, and Dancer in the Dark, a film that makes my tear ducts hate me. These three films are called the Golden Heart Trilogy because each movie's protagonist is mentally incapable of rational thought, yet they are overwhelmingly loving and generous to others. Each film ends with the almost Christ-like protagonist suffering a terrible fate.

His other trilogies, while more loosely connected, also share similar themes. He has a paranoid detective trilogy from the late '80's and early '90's that shared many stylistic qualities, but his writing was not yet as unified and mature as it has become. His Dogville trilogy, which as of this review is not yet finished, shares the same protagonist through the films, but very different thematic material.

The trilogy he is working on now, beginning with the much misinterpreted Antichrist, is built around the philosophy that there is nothing worth loving in this world. The protagonists in both Antichrist and Melancholia deal with a depression that makes them immobile. Charlotte Gainsbourg's She in Antichrist is sent into her depression because she feels responsible for her son's accidental death. Her suffering has a concrete cause, a catalyst, that the audience can relate to and sympathize with.

Kirsten Dunst's Justine in Melancholia does not have such a good excuse. Of course, this does not make her depression any less serious, or real, but it does put the audience in a strange position. Unlike She, who is constantly reporting the reasons behind her feelings, Justine remains silent on the subject. When she does speak, she is lashing out against the people who are controlling her life. She is a character who almost defies sympathy. She is a box we can't open, just like the people in our lives who really suffer from this disease.

The film begins with a wedding, Justine's wedding, which has been meticulously planned by her sister, Claire, and we quickly realize that Justine is hiding a deep depression behind her smile. She constantly finds reasons to escape the house, the spotlight, her sister, her new husband. She is suffocated by the ritual of the wedding, by the people who surround her. She doesn't want any of it and she doesn't know how to tell them.

|

| One of the first shots of the film |

Okay, I lied. The film actually begins, as Antichrist does, with a beautifully shot, slow-motion prologue. In the opening shot, Justine has electricity shooting from her fingers and Claire is running across a golf course, sinking into the grass, holding her son. A giant planet is looming over Earth, twenty times its size, sucking the atmosphere into its oceans. And then Melancholia, the titular planet, smashes into Earth, exploding it.

We get all of this before a single line of dialogue is spoken. Just a few extraordinarily staged shots (most of which can be spotted in the trailer) and one terrifying vision of the end of the world.

And then the wedding starts. Tens of characters are introduced, not unlike the very best Robert Altman films of the early seventies, and something weird happens. For the first time in a Lars Von Trier film, I had a lot of fun. There is humor and warmth to the first half of this film. Apart from, you know, the destruction of the planet. John Hurt plays a lovable grandfather, Keifer Sutherland plays an arrogant, rich scientist who is trying to please his unpleasable sister, Udo Kier plays a tragically underutilized wedding planner, Stellan Skarsgaard plays a hilariously forthright advertising agent, and the list goes on. The characters are all written quite well, and the scenes often play like the very best sections of Nashville.

It's a little stunning how warm and funny the first half of the film really is, considering how dark and nihilistic the films final half becomes. This tonal shift is placed almost completely on Dunst's performance, which is, I have to say, remarkable. I have never really seen true talent in Dunst before. She's passable, but I've mostly written her off as beautiful and one-note. But here, she is really doing something special. She is given the almost impossible task of carrying the ridiculous ambition of Von Trier's script, which includes tens of characters, an apocalyptic, science-fiction plot, and wild tone shifts between light-hearted comedy and deeply moving chamber drama.

I'm not sure how Trier knew she could do it, but she can. And not only is her performance adequate for the film, it's really one of the more nuanced and profound performances I've seen in quite some time. Meryl Streep might be the queen of impersonation and accents, but Kirsten Dunst is the one to beat during this year's awards season. Her performance is stunning.

The other performers do a good job, particularly Charlotte Gainsbourg, who is relegated to playing what is essentially the audience. Justine's brick wall of emotion is so indecipherable that Trier had to add a character who substitute's all of Justine's emotions for us.

For the last couple of decades, Lars Von Trier has been writing and directing films that show us exactly what he is afraid of. He is famously scared of everything, having never ridden an airplane in his life, or gone overseas, or even left Europe. He has attempted suicide, accepted Hitler into his heart, and forced Bjork to quit acting, and yet he continues on in his quest to make the world's bleakest movie. I thought that maybe Antichrist, in all of its excruciating, violent, and upsetting glory, was the end result of this quest.

I was wrong.

Melancholia is. And it is also the most brilliant movie of his career.

I give Melancholia 9/10 electric fingers

[Note: One small problem I had with the film is that Claire and Justine are sisters, yet one of them has a French-British accent and one sounds like she's from Maryland. Their parents are both British, as well as pretty much everybody else in the movie who isn't Keifer Sutherland. But I got over it.]

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Movie Review: Take Shelter

Michael Shannon's eyes have been put to great use in the last decade. You might know him from Revolutionary Road, where he was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his portrayal of John Givings, the math professor who has had a psychotic break. Sometimes actors are just born to play a certain type. Tim Blake Nelson has made an excellent career of playing rural idiots, Michael Douglas has made his fortune playing high-class snobs. The list goes on.

Of course, there are certain pitfalls to this kind of typecasting. For every George Clooney, where variations on a theme can lead to exciting and surprising results, there is always a Michael Ironside, where the performer is forced to play one note parts until they retire.

For a while there it was looking like Michael Shannon was going to be stuck in the latter category, forever playing the crazy uncle or the unhinged friend. However, in the last few years, Shannon has done a remarkable job of taking challenging roles that compliment his interesting face and physicality. Take his performance in the underrated masterpiece BUG, where his intense eyes almost make us believe in the insects we can't see. Or his performance in 2009's brilliant My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?, where Shannon's performance teeters somewhere between Marlon Brando and Bela Lugosi (no small feat), while simultaneously allowing us to project our own fears and desires onto him.

It seems that directors have taken note of Shannon's ability to convey emotion without speaking. Perhaps more than any other actor working today, Michael Shannon is the one most suited for silent pictures. His performances are always both understated and bombastic, playing with the balance of the two the way a good musician juggles improvisation and precision.

And in Jeff Nichols' atmospheric, devastating Take Shelter, Michael Shannon has given us the performance of his career.

Not since There Will Be Blood have I seen a performance that truly frightened me in this way. Shannon is so believable, so truly unhinged, that I often found myself shaking my head in disbelief. Every movement of his eyes and every twitch of his face has true power. He has mastered the physicality of his performance in such a unique and brilliant way that I could not take my eyes off the screen. He is electric here. Terrifying. I believe every second of his performance, and I can't wait to see what he does with the General Zod in Zack Snyder's upcoming Man of Steel.

As for the film itself, I'll give you a little background. If you haven't seen the chilling trailer yet, here's a quick summary of the plot. Curtis has been having nightmares for the last few weeks. Each one contains a storm. Whenever the storm comes, something happens to his daughter. The dreams become more vivid and violent as the film goes on, and his visions of the apocalypse begin to invade his waking life. Before long, it becomes unclear as to whether Curtis is truly having visions or just succumbing to mental illness.

Jeff Nichols' script and direction are incredibly ambitious for the obviously low budget on this film, and his script does a very good job of slowly building the suspense and the macabre atmosphere of the whole thing. The cinematography is still, deliberate, and the shot composition always leaves the main focus of the frame just a little bit obscured. As the film is told through the perspective of Curtis, Nichols uses the cinematography to limit the audience. We aren't allowed to know what Curtis does not, and Nichols wisely leaves it up to us to decide if Curtis is a prophet or just insane.

The other standout performance in this film is by The Tree of Life and The Help's Jessica Chastain, who seems to have come out of nowhere this year and surprised everyone with three excellent performances in a row. As Curtis' wife, Samantha, Chastain must perform the hardest job in the film--that is, play opposite such a juicy, provocative role and still maintain the audience's attention. And not only does she hold her own next to Shannon's powerhouse performance, but she sometimes exceeds even his abilities and reaches amazing heights. Nichols better be glad he got Chastain when he did, because she is bound for great things in the coming years--and even greater paychecks.

Of course, Take Shelter isn't perfect. It is a little overwritten, running perhaps fifteen minutes too long, and sometimes the plot beats are a little predictable, but when this film is in its stride, there is really nothing like it. It is haunting, emotional, honest, and, most of all, ambitious.

See it for Shannon's performance. It is one of the great performances of our time.

I give Take Shelter 8/10 Spooky Dream Sequences

Friday, November 25, 2011

Movie Review: Hugo

Let's talk about 3-D. For years, I've been saying that 3-D works best with animation. I've also been saying it should not be treated as a gimmick, but as an element. A tool. Like color, which quickly became the norm of cinema, 3-D should be used as one gear in a large machine. Animation seems to handle this philosophy best, seeing as computer animation has only recently gone from gimmick status to element status in the last decade.

3-D is commonly employed poorly in live action films. It sometimes works well, Avatar being a nice example (although, really, one could easily consider Avatar a computer animated film), but it is usually used for movies that would otherwise have nothing interesting to offer. The producers fund a lousy film under the promise that the swords will come flying out the screen and the three to four dollar surcharge will come flying out of wallets, not because the film's story can be modified in any way by this extra dimension. Avatar made such an impact because the world James Cameron created felt completely immersive. The film was about virtual bodies becoming real, dreams becoming tangible. The third dimension added a layer of depth to the overall intent of the film. I cannot say the same for The Green Hornet, Clash of the Titans, The Last Airbender, or any other totally valid reasons that people often give for not liking 3-D. Why pay the extra money? It's never worth it.

Here's the problem. 3-D technology is extremely impressive. When used effectively, the technology can add depth and wonder to the cinematography of a film. However, when used poorly, the technology faces extinction. We are in a transitional period. Like the introduction of color, we are faced with low-caliber variations of a phenomenal tool. For instance, many people believe that The Wizard of Oz was the first color film. It wasn't. People just believe that because the color was used to aid the story, to give the land of Oz depth, and to show people how the technique can revolutionize the way moving pictures can be experienced.

In a way, this is the story of film. When the Lumiere brothers made their first film of a train moving toward the camera, filmmaking was seen as a triviality. A sideshow gimmick. It took decades for film to be as respected as it is today. And, in some circles, film is still not quite as appreciated as literature or painting.

Which brings us to Hugo.

Martin Scorsese has made a name for himself in recent years for spearheading an ambitious film preservation society. He has given numerous talks, and made several documentary shorts, in order to spread the news that old films are disappearing each day. And, as one of the most knowledgeable film historians in the world, Scorsese has done pretty well with the campaign. And when I saw Scorsese's masterful, gorgeous new film Hugo, I couldn't help but wonder if any other filmmaker could have pulled off such a watchable educational film concerning cinema preservation.

Movies are at the heart of Hugo, Scorsese's first 3-D film, and he uses the medium not only to wow audiences with impressive visuals, but to also comment on the film's overall message.

The film concerns a forgotten silent filmmaker whose entire filmography has been destroyed for the sake of shoe heels (it makes sense in the movie), and how devastating this treatment of film was to the genius filmmakers who were left behind after the world wars.

Hugo is about film as an art form. It is about the director as artist. It reminds us that there was a time when special effects were new. That the visual wizardry of filmmaking was once shocking, surprising, awe-inspiring. That filmmakers used to be scoffed at for making populist drivel, even while they were producing some of the most incredible work of any artist at the time. At its heart, Hugo is about the relationship between an artist and his/her tools. For the early filmmakers, their tool was considered nothing more than a gimmick, a phase, a temporary distraction from real art. And, as I said earlier, 3-D is the new gimmick.

Scorsese, one of the most celebrated living filmmakers, was criticized for choosing to make his newest film in 3-D. The fad, as some say, has worn out its welcome. I beg to differ. The fad is not wearing out its welcome, bad use of the technique is. Now that we're finally getting master filmmakers behind 3-D cameras (Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, to name some Germans), audiences can now decide for themselves whether 3-D is their thing.

Hugo utilizes 3-D in a way that I have never seen outside of a theme park. The opening shot actually turns your stomach, in the best way possible, when it zooms through a busy train station and weaves around halls and ladders. The photography is kinetic and exciting. The depth is incredible, the shot compositions perfectly suited to the technology, and Scorsese feels right at home with the extra responsibility.

Also at home are Asa Butterfield and Chloe Moretz, the two young leads of the film. Butterfield in particular, as the titular character, brings warmth and emotion to his role--much needed elements for the mostly silent performance he gives. Moretz plays the opposite of her Kick-Ass character, Hit Girl, as she is an innocent, bookish girl who is terrified of getting into mischief. Moretz grounds the film with her calm, old-soul presence. The two leads play well off of each other, and they are benefitted from the excellent script by John Logan.

Hugo is a beautiful film. I highly recommend that you go see it, and I cannot stress enough how great the 3-D is here. But you have to meet the film halfway. If you don't want 3-D to be used as a gimmick, don't expect it to act like one. The extra dimension is just that, an extra dimension. This does not mean stuff flies in your face constantly. This means that there is an extra layer of depth to the screen. The shot compositions have become more complicated, and more interesting, because of this technology. Okay? Okay.

I give Hugo 9/10 released Krakens

3-D is commonly employed poorly in live action films. It sometimes works well, Avatar being a nice example (although, really, one could easily consider Avatar a computer animated film), but it is usually used for movies that would otherwise have nothing interesting to offer. The producers fund a lousy film under the promise that the swords will come flying out the screen and the three to four dollar surcharge will come flying out of wallets, not because the film's story can be modified in any way by this extra dimension. Avatar made such an impact because the world James Cameron created felt completely immersive. The film was about virtual bodies becoming real, dreams becoming tangible. The third dimension added a layer of depth to the overall intent of the film. I cannot say the same for The Green Hornet, Clash of the Titans, The Last Airbender, or any other totally valid reasons that people often give for not liking 3-D. Why pay the extra money? It's never worth it.

Here's the problem. 3-D technology is extremely impressive. When used effectively, the technology can add depth and wonder to the cinematography of a film. However, when used poorly, the technology faces extinction. We are in a transitional period. Like the introduction of color, we are faced with low-caliber variations of a phenomenal tool. For instance, many people believe that The Wizard of Oz was the first color film. It wasn't. People just believe that because the color was used to aid the story, to give the land of Oz depth, and to show people how the technique can revolutionize the way moving pictures can be experienced.

In a way, this is the story of film. When the Lumiere brothers made their first film of a train moving toward the camera, filmmaking was seen as a triviality. A sideshow gimmick. It took decades for film to be as respected as it is today. And, in some circles, film is still not quite as appreciated as literature or painting.

Which brings us to Hugo.

Martin Scorsese has made a name for himself in recent years for spearheading an ambitious film preservation society. He has given numerous talks, and made several documentary shorts, in order to spread the news that old films are disappearing each day. And, as one of the most knowledgeable film historians in the world, Scorsese has done pretty well with the campaign. And when I saw Scorsese's masterful, gorgeous new film Hugo, I couldn't help but wonder if any other filmmaker could have pulled off such a watchable educational film concerning cinema preservation.

Movies are at the heart of Hugo, Scorsese's first 3-D film, and he uses the medium not only to wow audiences with impressive visuals, but to also comment on the film's overall message.

The film concerns a forgotten silent filmmaker whose entire filmography has been destroyed for the sake of shoe heels (it makes sense in the movie), and how devastating this treatment of film was to the genius filmmakers who were left behind after the world wars.

Hugo is about film as an art form. It is about the director as artist. It reminds us that there was a time when special effects were new. That the visual wizardry of filmmaking was once shocking, surprising, awe-inspiring. That filmmakers used to be scoffed at for making populist drivel, even while they were producing some of the most incredible work of any artist at the time. At its heart, Hugo is about the relationship between an artist and his/her tools. For the early filmmakers, their tool was considered nothing more than a gimmick, a phase, a temporary distraction from real art. And, as I said earlier, 3-D is the new gimmick.

Scorsese, one of the most celebrated living filmmakers, was criticized for choosing to make his newest film in 3-D. The fad, as some say, has worn out its welcome. I beg to differ. The fad is not wearing out its welcome, bad use of the technique is. Now that we're finally getting master filmmakers behind 3-D cameras (Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, to name some Germans), audiences can now decide for themselves whether 3-D is their thing.

Hugo utilizes 3-D in a way that I have never seen outside of a theme park. The opening shot actually turns your stomach, in the best way possible, when it zooms through a busy train station and weaves around halls and ladders. The photography is kinetic and exciting. The depth is incredible, the shot compositions perfectly suited to the technology, and Scorsese feels right at home with the extra responsibility.

Also at home are Asa Butterfield and Chloe Moretz, the two young leads of the film. Butterfield in particular, as the titular character, brings warmth and emotion to his role--much needed elements for the mostly silent performance he gives. Moretz plays the opposite of her Kick-Ass character, Hit Girl, as she is an innocent, bookish girl who is terrified of getting into mischief. Moretz grounds the film with her calm, old-soul presence. The two leads play well off of each other, and they are benefitted from the excellent script by John Logan.

Hugo is a beautiful film. I highly recommend that you go see it, and I cannot stress enough how great the 3-D is here. But you have to meet the film halfway. If you don't want 3-D to be used as a gimmick, don't expect it to act like one. The extra dimension is just that, an extra dimension. This does not mean stuff flies in your face constantly. This means that there is an extra layer of depth to the screen. The shot compositions have become more complicated, and more interesting, because of this technology. Okay? Okay.

I give Hugo 9/10 released Krakens

Friday, November 11, 2011

Cameron Cook Music Company: My current favorite albums

|

| Parody? It's up to you. |

Okay, to be fair, there are some good tracks on Lynch's LP, which dropped earlier this week, but the other tracks are plagued by a hollow core. Lynch is a filmmaker first. That is his true talent. He can play a mean guitar, he can create an excellent aural texture, but he does not understand what it takes to craft an album. At least not yet. But Karen O. tried. And that's all that counts.

So here we are. In a world where David Lynch, one of the premier American filmmakers, retires from the medium that made him famous so he can sing into a vocoder about red shirts. And on top of that, your favorite movie blog just released an article on music. It's a sad day. But chin up, because you might find yourself downloading these artists on itunes before you know it.

My fifteen favorite albums of all time (in no order)

The Final Cut--Pink Floyd

Even though I can safely tell you that nostalgia is 50% of the reason behind this album's inclusion, I can still get behind some of the tracks. Pink Floyd (lets face it, Roger Waters for this one) managed to somehow make an entire album predicated on one emotion--fierce devastation. Every song has the emotional capacity of an entire Lars Von Trier film in only three minutes. The title track is still a favorite of mine, even after all these years, for its sheer arena-rock balladry. While this album is certainly a departure for the band that brought you "Jugband Blues," it's also a real treat for those who want a good cry. Highly recommended.

TOP TRACKS: The Final Cut, Your Possible Pasts, The Fletcher Memorial Home

Have One On Me--Joanna Newsom

I had a summer vacation a couple of years back where I delivered pizza for Pizza Hut. It was not a very fun job, but it had one undeniable perk. I got at least three hours a day, for an entire summer, of music enjoyment in my car. However, as I was working one of the more dangerous jobs around, I decided that taking my iPod to work was probably a bad idea. So I listened to CD's the old fashioned way. This made me appreciate the strength of the album again. Not only that, but it forced me to choose more wisely. So when I bought Joanna Newsom's follow up to her beautiful Ys (introduced to me by Allen Butt), it was mostly because the thing is a TRIPLE ALBUM that spans over two hours. I needed a long album to fill my time. I listened to it once. Then twice. Then over fifty times. Every time I hear it I get something new from it. The lyrics, the instrumentation, the atmosphere. Everything about the album is fresh and exciting and brilliant.

TOP TRACKS: '81, Go Long, Jackrabbits, Esme

The Age of Adz--Sufjan Stevens

Where was he supposed to go after the jaw-dropping double threat of Come On Feel The Illinoise and The BQE? What was Stevens's next logical step? Famous for his broad instrumentation and huge sound, Stevens really swung for the fences with this one. While many fans argue that he relies too much on noise and distortion on this outing, I find the fuzzy, crowded atmosphere to be just right for the singer/songwriter. His lyrics, the most personal and cynical of his career, perfectly marry the digital whirrs and buzzes that Stevens supplies. It addresses his fame, the expectations of his fans, his ego, his religious demons. The album is Stevens's most interesting, and arresting, work so far.

TOP TRACKS: Vesuvius, All For Myself, Futile Devices, Impossible Soul

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy--Kanye West

My jaw dropped when I heard this album for the first time. It is, without a doubt, the most maximalist music produced for commercial artists that I've ever heard. In many ways, Fantasy is not so different from Age of Adz. They're both filled to the brim with noise, voices, and emotions. They're both produced by guys who have written entire albums about Illinois. They're both musicians who address their personal demons directly in their lyrics. Their egos often control their production. I've been a casual fan of Kanye for a few years. Since high school, around the time Late Registration dropped, I've been fascinated by West's ability to make his innermost fears and regrets the highlights of his albums. He is a true pop star, the most interesting pop star working today, because he is a real person. He's a jerk, a genius, a child. He's defensive about his music, his mother, his intelligence. Fantasy is the album he's been trying to make for ten years, and it does not disappoint. It is one of the finest albums I've ever heard.

TOP TRACKS: Monster, Runaway, Lost in the Woods, Blame Game

Fever Ray--Fever Ray

Karin Andersson's side-project is, in my opinion, far more interesting than Andersson's "real" band, The Knife. Not because Fever Ray is necessarily better, but because it is a stronger expression of Andersson's abilities as a producer. The Knife, known for its catchy, '80's-loving indie-electronica sound has its own thing going on. The Knife is all about exuberance and living in the moment. Fever Ray, on the other hand, is a bit darker. A bit more unsettling. So of course I love it. The album is packed with eerie soundscapes and mysterious lyricism. It is about loneliness, despair, growing up, dying. The album is also just that, an album. I can't listen to just a couple of tracks from this masterpiece, it is made to be listened to all the way through.

TOP TRACKS: If I had a Heart, Seven, Keep the Streets Empty for Me

Stop Making Sense--Talking Heads

There are few things David Byrne can't do. Make a terrible live album is one of those things. Stop Making Sense is not only the perfect setlist made during the peak of Talking Heads' talent, but the album itself works as the single best introduction to the Talking Heads possible. Match the album's amazing setlist with the fact that it is a miraculously good concert film, and you've got yourself a Friday night.

TOP TRACKS: Heaven, Once in a Lifetime, This Must Be the Place(Naive Melody), Found a Job

Live At The Royal Albert Hall--Bob Dylan

We all know that Dylan went electric. We all know about the uproar. We know the history. But sometimes you need to experience these things for yourself. Dylan's 1966 performance in the Royal Albert Hall is unmatched when it comes to live albums. The first set, all acoustic, displays his excellent showmanship and (yes, I'm serious) his amazing vocals. He doesn't need to be classically trained. He doesn't need an objectively fantastic voice to be a fantastic vocal performer. The songs weren't written for that. It's an Americana groan, a tired dust bowl cry. His voice in this performance is stunning. The second half of the album is his electric set. The audience goes wild. The famous "JUDAS!" shout can be heard during this set. It is a perfect live album. The best possible display of Dylan's amazing talent.

TOP TRACKS: It's All Over Now, Baby Blue, Mr. Tambourine Man, Ballad of a Thin Man

In The Aeroplane Over The Sea--Neutral Milk Hotel

You knew this was coming. It's the Citizen Kane of albums. Everybody's favorite. But for good reason, the thing is sensational. The lyrics, the vocals, the song structure. It's a masterpiece. Whenever I listen to "Oh Comely" I can do nothing but marvel at Mangum's words. It is a magnificent piece of writing.

TOP TRACKS: Oh Comely, Two-Headed Boy Part 2

Achilles Heel--Pedro The Lion

Everybody has an album that speaks to them. An album that feels like it took all of your beliefs, fears, regrets, and desires and turned them into a forty minute experience. This is that album for me. From "Bands with Managers" to "The Poison," Pedro the Lion's album is about contentment, and how contentment can spread like a disease. Everything from Bazan's vocals to the tight musicianship of the band to the song structure to the song order of the album is as perfect as I've ever seen. On most days I consider this the best album I've ever heard.

TOP TRACKS: Bands With Managers, Arizona, Start Without Me

Songs From a Room--Leonard Cohen

Cohen's follow up to his debut album is a more somber, lonely kind of album. Even for him. Although his guitar is backed by a full band this time around, the album still seems sparse. Minimalist, even. There are moments in the album, such as the French chorus in "The Partisan," where the music escapes the titular room and reaches out beyond the desolation that Cohen so famously describes in his lyrics. But these moments only serve to make the listener more aware of how contained the album really is. In the tragic, beautiful song "Seems So Long Ago, Nancy," Cohen describes a suicide, and its reasons, in grim detail and with sentiment. It is Cohen's breathtaking lyricism that escalates his unapologetically rough vocals. His nonchalance to it all is the reason these songs have so much impact. Yes, these things happen. But they're going to happen again.

TOP TRACKS: The Butcher, Tonight Will Be Fine, The Partisan

Celebration, Florida--The Felice Brothers

It didn't take long for this one to become my favorite. The Felice Brothers have been among my go-to bands for a while now. The storytelling aspect of Ian Felice's lyrics proves to be a good fit with me. As you've probably guessed, I enjoy me a slow, wordy song. But this album is something special. It contains similar elements to the Brother's previous work, but it's just a little unhinged. The album is angry, possessed by cynicism, jaded. Its title, named after the town Walt Disney founded near Disney World, was picked after that town had its first murder last year. It was an ax murder. Ian's lyrics cover everything from Honda Civics to Oliver Stone to Ponzi Schemes to the weight of expectation from fans. This album is loud, angry, experimental, and brilliant.

TOP TRACKS: Fire in the Pageant, Ponzi, River Jordan

Bone Machine--Tom Waits

Like Bob Dylan, Tom Waits tries to do something a little different with each of his albums. With Mule Variations, waits went for the dust bowl sound. In Rain Dogs, Waits tried to recreate the immigrant experience, and so on. Bone Machine is his album about death. From the opening track "Earth Died Screaming," there is no mistaking the album's apocalyptic themes. Waits waxes poetic about various aspects of death, ranging from bodies turning into dust to the tragedy of dying young. He rants about not wanting to grow up and get old. He refers to bodies as machines made of bone, performing their functions until they have to shut down. However, even with the somber subject matter, Waits finds a way to make it fun with his inventive percussion and beautiful songwriting.

TOP TRACKS: Earth Died Screaming, Who Are You?

Nebraska--Bruce Springsteen

You guessed it, my favorite album from arena-rocker's vast discography is his most quiet, moody, and wordy. Originally recorded as demos for a later, E Street Band album, Springsteen found himself writing from an introspective, singer/songwriter place instead. Songs like "Nebraska" and "Atlantic City" started spilling out of him, and he decided to just roll with it. Nebraska is about the American heartland, and how all is not well. The titular track covers the same ground as the Terrence Malick film from which it is based, Bandlands, and it details the murderous road trip of a young couple across the Nebraska badlands. The album plays off of Springsteen's fear of loneliness, regret, solitude. It is sparse and uncompromising. A great album.

TOP TRACKS: Nebraska, Atlantic City, Highway Patrolman

The Crying Light--Antony & The Johnsons

Even Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen fans need to hear some beautiful singing every now and then. It's a good thing Antony's around. The piano-playing, falsetto singing, lyrical genius that is Antony Hegarty really swings for the fences on this release. He speaks about nature, gender (Antony himself is transgender), love, abandon, God, and death with such confidence and such beauty that it is impossible not to believe him. The instrumentation alone is absolutely gorgeous. Pure ear candy.

TOP TRACKS: Aeon, Daylight and the Sun, The Crying Light

Breach--The Wallflowers

Breach is one of those albums I can listen to at any time and get into. Long after "One Headlight"'s radio omnipresence left the country, frontman Jacob Dylan (son of Bob) wrote the songs that would end up on this album. It still has that groovy '90's sound, but the lyricism is much more aggressive and dirty. The sounds are catchy, maddeningly so, and the album is really meant to be played as a unit. For this reason, no real singles came out of this bad boy. And that's a shame, because the album is really pretty amazing.

TOP TRACKS: Hand Me Down, Witness, Birdcage

What are some of your favorite albums? Let me know in the comments below or on Facebook!

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Unbalanced and Extraordinary: Dear Zachary

Kurt Kuenne's documentary, Dear Zachary, is all at once amateur, over-the-top, subjective, sentimental, horrifying, beautiful, and unfinished. The first thing you notice about the film is that it is small. It was made on a shoe-string budget by a friend of the Bagby family and was edited over the course of several years.

The film's structure is unsound. Sometimes the looseness of the film feels intentional. There are scenes where the narration is the only thing keeping it together, as if a mistake in the filming forced the documentary in a direction that Kuenne was uncomfortable taking. There are interviews that are ripped to shreds in the editing because it's clear that the wrong questions were asked. The timeline moves back and forth with no order. Inserts of home movies interrupt the flow of the film in ways that startle the viewer. The editing actually distracts from the picture, making everything feel crowded, fussy, and unprofessional.

When I started watching the film, I realized that there was a serious problem. It begins with a narration by Kuenne where he describes his relationship with the subject of the film. The subject, Andrew Bagsby, was murdered in the early 2000's, and Kuenne decided to make a film in tribute to Andrew by documenting the years following his death. The film includes hundreds of interviews and home movies concerning Andrew. It becomes clear early on that Kuenne's affection for Andrew is strong, perhaps too strong, for the kind of documentary it appears to be.

The film--at least the first half--is a parallel narrative that documents Andrew's early life as well as the investigation of his murder. While the bits about his early life are charming, they definitely lean on the side of sentimental. Swelling piano music fills the soundtrack every time somebody mentions Andrew, and this style begins to wear on the viewer. The film tries too hard to make us immediately love Andrew, and it seems to not trust that we can do it on our own without the amateurish techniques employed by the filmmaker.

However, I decided to keep watching, seeing as the film has been getting rave reviews almost unanimously for three years. And I'm happy that I did.

To be clear, the film is not kidding. Its sentimentality is sincere, almost too sincere, and in this way the final half of the film is a devastating blow. I don't want to spoil the story for you, as the development of the increasingly complicated plot is half of the brilliance of the documentary, but I will say that Dear Zachary turns into a surprisingly upsetting, and shocking, piece of documentary filmmaking.

It takes on an impressionistic form. The awkward editing and schmaltzy piano is turned against the viewer as the film continues. As Kuenne's story becomes more unbelievable, so, too, does the way in which he tells the story. The talking heads begin to speak over one another. Various visual and aural motifs begin to repeat themselves in interesting ways. The film begins to fold in on itself. Something magical happens.

What begins as a pretty standard dateline episode turns into a wrenching true story told in an explosive way. That's not to say that the film doesn't have its problems, but that Dear Zachary is one of the more fresh documentaries I've seen in a while. And part of its excellence stems from its unpretentious style. From its unpolished esthetic.

I highly recommend the film, which is on Netflix Watch Instantly, and runs 90 minutes.

I give it 7/10 excellent second acts.

The film's structure is unsound. Sometimes the looseness of the film feels intentional. There are scenes where the narration is the only thing keeping it together, as if a mistake in the filming forced the documentary in a direction that Kuenne was uncomfortable taking. There are interviews that are ripped to shreds in the editing because it's clear that the wrong questions were asked. The timeline moves back and forth with no order. Inserts of home movies interrupt the flow of the film in ways that startle the viewer. The editing actually distracts from the picture, making everything feel crowded, fussy, and unprofessional.

When I started watching the film, I realized that there was a serious problem. It begins with a narration by Kuenne where he describes his relationship with the subject of the film. The subject, Andrew Bagsby, was murdered in the early 2000's, and Kuenne decided to make a film in tribute to Andrew by documenting the years following his death. The film includes hundreds of interviews and home movies concerning Andrew. It becomes clear early on that Kuenne's affection for Andrew is strong, perhaps too strong, for the kind of documentary it appears to be.

The film--at least the first half--is a parallel narrative that documents Andrew's early life as well as the investigation of his murder. While the bits about his early life are charming, they definitely lean on the side of sentimental. Swelling piano music fills the soundtrack every time somebody mentions Andrew, and this style begins to wear on the viewer. The film tries too hard to make us immediately love Andrew, and it seems to not trust that we can do it on our own without the amateurish techniques employed by the filmmaker.

However, I decided to keep watching, seeing as the film has been getting rave reviews almost unanimously for three years. And I'm happy that I did.

To be clear, the film is not kidding. Its sentimentality is sincere, almost too sincere, and in this way the final half of the film is a devastating blow. I don't want to spoil the story for you, as the development of the increasingly complicated plot is half of the brilliance of the documentary, but I will say that Dear Zachary turns into a surprisingly upsetting, and shocking, piece of documentary filmmaking.

It takes on an impressionistic form. The awkward editing and schmaltzy piano is turned against the viewer as the film continues. As Kuenne's story becomes more unbelievable, so, too, does the way in which he tells the story. The talking heads begin to speak over one another. Various visual and aural motifs begin to repeat themselves in interesting ways. The film begins to fold in on itself. Something magical happens.

What begins as a pretty standard dateline episode turns into a wrenching true story told in an explosive way. That's not to say that the film doesn't have its problems, but that Dear Zachary is one of the more fresh documentaries I've seen in a while. And part of its excellence stems from its unpretentious style. From its unpolished esthetic.

I highly recommend the film, which is on Netflix Watch Instantly, and runs 90 minutes.

I give it 7/10 excellent second acts.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Halloween Blog Month: My Favorite Horror Films

My relationship with Horror is tricky. While it's a genre I particularly like, I usually walk away feeling cheated and angry. Horror has a way of playing to the lowest common denominator. This means that Horror is usually, on a maturity level, about even with anything from the Happy Madison production company. But when I find that diamond in the rough, that rarest of precious stones, the good Horror film, I cherish it for years and years.

Here are ten Horror films I can usually rely on. For list purposes, I'm leaving out The Exorcist, The Shining, The Blair Witch Project, Rosemary's Baby, Carnival of Souls, and Night of the Living Dead. You've seen them, I've seen them, we've all seen them. We all know they're good. My number 10 is a little iffy too. But hey, here it is:

10) Evil Dead 2

Sam Raimi's fantastic Horror/Comedy sequel is one of the most crowd-pleasing of all crowd pleasers. This movie gets better and better every time you see it. The camera work, the acting, the writing, the crazy effects. It all works. Army Of Darkness is also highly recommended. While the film isn't really all that scary, it makes up for it with the amount of fun it has with the genre.

9) [Rec]

[Rec] is one of those Horror movies that sneak up on you. What at first feels like a pretty standard "found footage" flick becomes an immensely frightening, and surprising, real-time pot-boiler. It begins with a woman trying to find something interesting to film for her after-dark news series. When she decides to follow some firemen to a routine rescue, she quickly finds herself in a dangerous quarantine zone.

The film's use of its set design is truly mesmerizing. The apartment complex becomes a character in itself. There was an American remake of this film recently that did an okay job of recreating the magic of [Rec], but there's just something about the end that doesn't compare to the Spanish-language original. The last five minutes are truly frightening.

8) Trick'r Treat

Trick'r Treat is one of those rare short film anthologies that actually work. The films congeal. They are the separate limbs of a tree. Too often, these short film anthologies feel too disjointed and tonally dissimilar to be tacked to one another. When Trick'r Treat was brought to my attention last year, I couldn't help but feel like the movie would disappoint. Its distributor had decided to pull it from a theatrical release, last minute, in order to send it straight-to-DVD, the writer and director, Michael Dougherty, hadn't really proved himself in any significant way yet, and the overall story (plus marketing) are pretty dreadfully displayed.

However, despite all of this, I found a way to really dig this movie. It knows what it's all about. There is a strange tone to it. It is a very funny Horror movie, but it's not really a Horror/Comedy. The stories work together to create this wacky Halloween film that exists in its own special world. As if Raising Arizona were made into a Horror film, but kept its zany logic intact. I'm going to make this movie a yearly event.

7) The King of Comedy

Martin Scorsese's often overlooked masterpiece is also often overlooked as a comedy. While, yes, the film does use the word comedy in its title, have Jerry Lewis in its cast of characters, and center on a stand up comedian, the movie is really only kind of funny. The humor is dark, twisted, and mean. Robert DeNiro's Rupert Pupkin is only funny in that he doesn't really exist. Jerry Lewis' version of Jerry Lewis is only funny because we all know that Jerry Lewis truly is a mean, narcissistic comedian.

In reality, The King of Comedy is a much less optimistic version of Taxi Driver. You read that correctly. While Taxi Driver has that little bit of redemption at the end, what does Rupert Pupkin have by the end of King of Comedy? The movie is a dark portrait of a man who wants nothing more than to be laughed with. He wants to be in on the joke, but he is always the butt of it. DeNiro's performance is sad, pathetic, terrifying, and, yes, a little funny.

I recommend you check it out immediately. It should be more popular than it is.

6) The Devil's Rejects

Something happened to Rob Zombie between House of a 1000 Corpses and The Devil's Rejects. While the former film seemed rambling and adolescent, the latter film feels like an absolute explosion of raw talent. The key word here is raw. The Devil's Rejects is, admittedly, totally disgusting, but it is also kind of charming. The characters are full and dynamic. They love each other. They have senses of humor about their day jobs. You come to truly care for them. And after you see the kinds of things they do in this movie, you really come to appreciate the level of skill Rob Zombie has as a director.

I will be the first to admit that Rob Zombie is a horrible screenwriter. But what he lacks in his writing talents he more than makes up for with his casting, direction, and music choices. This movie has a killer soundtrack. And when the actors say their terrible dialogue, they do it with such conviction that you can almost believe it. There's just something whimsical about this film that Zombie has not been able to capture in his other efforts. It's so off the cuff, so unpretentious, so totally raw, that it is hard to find fault with it. It is one of the truest expressions of Horror filmmaking I've seen in some time. It's not for everybody, that's for sure, but The Devil's Rejects is definitely better than it needs to be.

5) Martyrs

The hallmark of any good horror film is its ability to cause discomfort. There is the cheap route, where gore and violence become a quick way to make moviegoers barf, and there is the effective route, where the film takes its time to prove itself. Where it makes you fall in love the characters and fear for them. A good Horror film stirs something inside of you. It takes your fears and turns them against you. It forces you to question disturbing topics.

Martyrs is in the latter category. While it is true that Martyrs has some of the most disturbing images of gore I have ever witnessed, it is not reliant on that gore to manufacture its scares. Martyrs is a hopeless film. It is about a girl who escapes abuse and makes it her lifelong goal to find retribution. When she finally does get her revenge, a half hour into the film, the audience wonders where the film could possibly go from here. And it goes to a place you never would have expected. The film is beautifully shot. The acting is superb. And the scares genuinely unnerve you. No matter how many "serious" critics dismiss the film as nothing more than a torture porn trifle, there really is something to Martyrs. In a way, it is a beautiful film. But it is also nihilistic as all get out.

Martyrs is for the brave. Be warned.

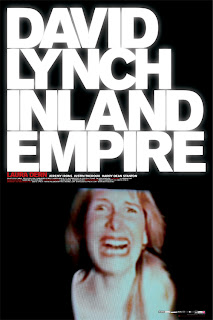

4) Inland Empire

I think I've said enough about this movie, but I'm going to say some more. If you let it, Inland Empire can really, really terrify you. Lynch takes almost every film convention and turns it on its head. He intentionally edits scenes of dialogue so that the moments of silence stretch into an eternity. He takes the convention of character continuity and spins it by making names and faces almost never match up. The visuals are fuzzy and unclear, breaking our HD-centric times. The film plays like a bad nightmare. It never fully makes sense. Its characters suffer and we don't know why.

And then there's that horrible shot of Laura Dern running toward the camera, her makeup running across her face, screaming.

Good luck.

3) Don't Look Now

You'd be hard-pressed to find a more atmospheric Horror film than this one. Nicolas Roeg's strange, hypnotic psycho-Horror about a married couple's slow descent into madness after the death of their daughter is truly a masterpiece of film editing. The entire film plays like the worst therapy session of your life. The film succeeds because of its truth. These are parents who are struggling with a very real fear. The characters are honestly and accurately portrayed.

The Venice setting adds another layer to the madness of the film. Its thousands of small alleyways and canals make the very setting something of a Jungian maze.

And that ending, my God, that ending.

Don't Look Now is not only one of the best Horror films I've ever seen, but one of the best films period.

2) Audition

Now that I've told you that Audition is a Horror film, it is much less likely to scare you. But don't let that fact deter you. This is one genuinely disturbing flick. What starts off as a kind of sweet little art film about an old man's search for love turns into a sort of poor attempt at a RomCom, which then turns into an excellent attempt at terrifying Horror masterpiece.

Takashi Miike does something amazing with Audition--he somehow combines an interesting, thought-provoking arthouse film with a Horror film final act that doesn't suck. While a lot of Horror films seem to fall apart and lose steam as they reach their conclusions, Audition only gets better and better. If you haven't seen this one, definitely look it up. I believe it is available as Watch Instantly on Netflix.

1) Benny's Video

Benny's Video is, without a doubt, the most disturbing film I have ever seen. This is because the film does not ever, at any time, ring false. Michael Haneke's direction is straightforward. At no time does the movie go out of its way to be theatrical. It merely is. And the bleak picture that it paints is enough.

The film is about a young man, Benny, who obsesses over violent videos in his bedroom. There is one video in particular, one where a pig is slaughtered, that he watches repeatedly. In a time where literally any form of violence can be found on the internet, this film is even more true, and even more bleak, in its representation of disillusioned youth.

Benny's obsession with the video leads him to make his own. He invites a cute girl over to his house, watches the video with her, sets up his own camera, and kills her. The shot is long. We watch her die and fall onto the ground. Benny cleans up his mess, hides the body, and watches the tape again.

The film makes a point to be untheatrical. It just exists. The shots last for several minutes at a time. The acting is incredibly minimalist. There are no consequences in the film. It is truly the bleakest, most disturbing Horror film I have ever seen. And it is also the best.

Honorable Mention

Santa Sangre

This film defies genre. But it is mostly Horror. It is on Netflix Watch Instantly. I suggest you just look up and watch it. You won't regret it.

What are some of your favorite Horror films? Let me know in the comments section or on Facebook.

Here are ten Horror films I can usually rely on. For list purposes, I'm leaving out The Exorcist, The Shining, The Blair Witch Project, Rosemary's Baby, Carnival of Souls, and Night of the Living Dead. You've seen them, I've seen them, we've all seen them. We all know they're good. My number 10 is a little iffy too. But hey, here it is:

10) Evil Dead 2

Sam Raimi's fantastic Horror/Comedy sequel is one of the most crowd-pleasing of all crowd pleasers. This movie gets better and better every time you see it. The camera work, the acting, the writing, the crazy effects. It all works. Army Of Darkness is also highly recommended. While the film isn't really all that scary, it makes up for it with the amount of fun it has with the genre.

9) [Rec]

[Rec] is one of those Horror movies that sneak up on you. What at first feels like a pretty standard "found footage" flick becomes an immensely frightening, and surprising, real-time pot-boiler. It begins with a woman trying to find something interesting to film for her after-dark news series. When she decides to follow some firemen to a routine rescue, she quickly finds herself in a dangerous quarantine zone.

The film's use of its set design is truly mesmerizing. The apartment complex becomes a character in itself. There was an American remake of this film recently that did an okay job of recreating the magic of [Rec], but there's just something about the end that doesn't compare to the Spanish-language original. The last five minutes are truly frightening.

8) Trick'r Treat

Trick'r Treat is one of those rare short film anthologies that actually work. The films congeal. They are the separate limbs of a tree. Too often, these short film anthologies feel too disjointed and tonally dissimilar to be tacked to one another. When Trick'r Treat was brought to my attention last year, I couldn't help but feel like the movie would disappoint. Its distributor had decided to pull it from a theatrical release, last minute, in order to send it straight-to-DVD, the writer and director, Michael Dougherty, hadn't really proved himself in any significant way yet, and the overall story (plus marketing) are pretty dreadfully displayed.

However, despite all of this, I found a way to really dig this movie. It knows what it's all about. There is a strange tone to it. It is a very funny Horror movie, but it's not really a Horror/Comedy. The stories work together to create this wacky Halloween film that exists in its own special world. As if Raising Arizona were made into a Horror film, but kept its zany logic intact. I'm going to make this movie a yearly event.

7) The King of Comedy

Martin Scorsese's often overlooked masterpiece is also often overlooked as a comedy. While, yes, the film does use the word comedy in its title, have Jerry Lewis in its cast of characters, and center on a stand up comedian, the movie is really only kind of funny. The humor is dark, twisted, and mean. Robert DeNiro's Rupert Pupkin is only funny in that he doesn't really exist. Jerry Lewis' version of Jerry Lewis is only funny because we all know that Jerry Lewis truly is a mean, narcissistic comedian.

In reality, The King of Comedy is a much less optimistic version of Taxi Driver. You read that correctly. While Taxi Driver has that little bit of redemption at the end, what does Rupert Pupkin have by the end of King of Comedy? The movie is a dark portrait of a man who wants nothing more than to be laughed with. He wants to be in on the joke, but he is always the butt of it. DeNiro's performance is sad, pathetic, terrifying, and, yes, a little funny.

I recommend you check it out immediately. It should be more popular than it is.

6) The Devil's Rejects

Something happened to Rob Zombie between House of a 1000 Corpses and The Devil's Rejects. While the former film seemed rambling and adolescent, the latter film feels like an absolute explosion of raw talent. The key word here is raw. The Devil's Rejects is, admittedly, totally disgusting, but it is also kind of charming. The characters are full and dynamic. They love each other. They have senses of humor about their day jobs. You come to truly care for them. And after you see the kinds of things they do in this movie, you really come to appreciate the level of skill Rob Zombie has as a director.

I will be the first to admit that Rob Zombie is a horrible screenwriter. But what he lacks in his writing talents he more than makes up for with his casting, direction, and music choices. This movie has a killer soundtrack. And when the actors say their terrible dialogue, they do it with such conviction that you can almost believe it. There's just something whimsical about this film that Zombie has not been able to capture in his other efforts. It's so off the cuff, so unpretentious, so totally raw, that it is hard to find fault with it. It is one of the truest expressions of Horror filmmaking I've seen in some time. It's not for everybody, that's for sure, but The Devil's Rejects is definitely better than it needs to be.

5) Martyrs

The hallmark of any good horror film is its ability to cause discomfort. There is the cheap route, where gore and violence become a quick way to make moviegoers barf, and there is the effective route, where the film takes its time to prove itself. Where it makes you fall in love the characters and fear for them. A good Horror film stirs something inside of you. It takes your fears and turns them against you. It forces you to question disturbing topics.

Martyrs is in the latter category. While it is true that Martyrs has some of the most disturbing images of gore I have ever witnessed, it is not reliant on that gore to manufacture its scares. Martyrs is a hopeless film. It is about a girl who escapes abuse and makes it her lifelong goal to find retribution. When she finally does get her revenge, a half hour into the film, the audience wonders where the film could possibly go from here. And it goes to a place you never would have expected. The film is beautifully shot. The acting is superb. And the scares genuinely unnerve you. No matter how many "serious" critics dismiss the film as nothing more than a torture porn trifle, there really is something to Martyrs. In a way, it is a beautiful film. But it is also nihilistic as all get out.

Martyrs is for the brave. Be warned.

4) Inland Empire

I think I've said enough about this movie, but I'm going to say some more. If you let it, Inland Empire can really, really terrify you. Lynch takes almost every film convention and turns it on its head. He intentionally edits scenes of dialogue so that the moments of silence stretch into an eternity. He takes the convention of character continuity and spins it by making names and faces almost never match up. The visuals are fuzzy and unclear, breaking our HD-centric times. The film plays like a bad nightmare. It never fully makes sense. Its characters suffer and we don't know why.

And then there's that horrible shot of Laura Dern running toward the camera, her makeup running across her face, screaming.

Good luck.

3) Don't Look Now

You'd be hard-pressed to find a more atmospheric Horror film than this one. Nicolas Roeg's strange, hypnotic psycho-Horror about a married couple's slow descent into madness after the death of their daughter is truly a masterpiece of film editing. The entire film plays like the worst therapy session of your life. The film succeeds because of its truth. These are parents who are struggling with a very real fear. The characters are honestly and accurately portrayed.

The Venice setting adds another layer to the madness of the film. Its thousands of small alleyways and canals make the very setting something of a Jungian maze.

And that ending, my God, that ending.

Don't Look Now is not only one of the best Horror films I've ever seen, but one of the best films period.

2) Audition

Now that I've told you that Audition is a Horror film, it is much less likely to scare you. But don't let that fact deter you. This is one genuinely disturbing flick. What starts off as a kind of sweet little art film about an old man's search for love turns into a sort of poor attempt at a RomCom, which then turns into an excellent attempt at terrifying Horror masterpiece.

Takashi Miike does something amazing with Audition--he somehow combines an interesting, thought-provoking arthouse film with a Horror film final act that doesn't suck. While a lot of Horror films seem to fall apart and lose steam as they reach their conclusions, Audition only gets better and better. If you haven't seen this one, definitely look it up. I believe it is available as Watch Instantly on Netflix.

1) Benny's Video

Benny's Video is, without a doubt, the most disturbing film I have ever seen. This is because the film does not ever, at any time, ring false. Michael Haneke's direction is straightforward. At no time does the movie go out of its way to be theatrical. It merely is. And the bleak picture that it paints is enough.

The film is about a young man, Benny, who obsesses over violent videos in his bedroom. There is one video in particular, one where a pig is slaughtered, that he watches repeatedly. In a time where literally any form of violence can be found on the internet, this film is even more true, and even more bleak, in its representation of disillusioned youth.

Benny's obsession with the video leads him to make his own. He invites a cute girl over to his house, watches the video with her, sets up his own camera, and kills her. The shot is long. We watch her die and fall onto the ground. Benny cleans up his mess, hides the body, and watches the tape again.

The film makes a point to be untheatrical. It just exists. The shots last for several minutes at a time. The acting is incredibly minimalist. There are no consequences in the film. It is truly the bleakest, most disturbing Horror film I have ever seen. And it is also the best.

Honorable Mention

Santa Sangre

This film defies genre. But it is mostly Horror. It is on Netflix Watch Instantly. I suggest you just look up and watch it. You won't regret it.

What are some of your favorite Horror films? Let me know in the comments section or on Facebook.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Halloween Blog Month: Modern Horror Vs. Modern Horror Fans

|

| Gross |

Modern Horror is all about butts in seats. But let's be honest, Horror is a genre's genre, and most of the people who produce it are in the field because they love dem seat butts. There is a formula, people. And that formula is easy for hacks to follow in order to make a quick buck. When people talk about the state of Horror films, they mostly speak from an "All is lost" perspective. The great Don't Look Now's of yesteryear are lost to buckets of blood and graphic torture. Where is the suspense! Where is the mystery! I've written a couple of blogs on the subject myself. And for a movie lover like me, it is painful to see other cinephiles scoffing at Horror films like they are the lowest form of entertainment. Even if they are.

Of course, when a Horror film does turn out to be good, its genre is always transferred to thriller. The Sixth Sense, The Silence of the Lambs, The Exorcist--all now widely written about as thrillers. Why? Because the very word, Horror, is demeaning to the film.

It reminds me of a joke from 30 Rock, where Alec Baldwin's character tries to stop Tina Fey from calling a man Mexican. "No, Lemon, don't call him that. That can't be what he wants to be called."

The fact is, Horror has always been a dead genre for film. Going as far back as Nosferatu, true cinema lovers often wonder why any intellectual would want to feel such a "feely" feeling as fear. Certainly tragic catharsis is the only true emotion an intellectual can have. But Tolstoy claimed that Comedy is for the intellectual and tragedy is for the commoner. Furthermore, an interesting thing about comedic films is that they are structurally quite similar to Horror films. Their purpose is similar as well.

I suppose I could write about the difference between the Saw franchise and the Paranormal Activity franchise as two ends of a Horror spectrum. One side being too gory and up-front, and one side being too slow expecting too much from too little. I suppose I could talk about Kevin Smith's newest film, Red State, and how it's trying to satire the very genre it becomes--and not very well. But I'm going to talk about something else instead. You've heard enough about these other things.

I want to talk about Horror fans.

More specifically, I want to talk about The Human Centipede (Full Sequence). Not because it's disturbing, disgusting, revolting, blah blah blah, but because it is extremely aware of the state of Horror fandom. And in this way (and, I promise, in this way alone), Tom Six's film is...kind of brilliant.

The first Human Centipede is a pretty standard torture porn film. It has the annoying young women, the creepy older villain, the gross-out shots of mouth-to-anus surgical binding. The usual suspects. Six's film is by no means the most repulsive movie I've ever seen (I'm looking at you Martyrs), but it is certainly in the same camp as something like High Tension or Inside.

The full sequence, however, is another beast altogether. It stars a man named Martin, fat, alone, sad, and the biggest Horror nerd you've ever met. He becomes obsessed with the original Human Centipede film and decides that he is going to attempt his own sequence. The film is shot in glorious black and white (to add an extra level of artifice) and uses unknown actors.

While the film kind of turns into one long poop joke, I can certainly appreciate what Tom Six is doing with the material. But I am also extremely upset by it. He is taking the common stereotype of a Horror nerd and putting him in the situation that the media absolutely loves to cover. This is the guy who shot his classmates because of Grand Theft Auto. He is the weak minded, highly malleable superfan that horror is famous for. He is the extremist.

Which brings me to my problem with the genre. Horror has some of the most devoted fanboys imaginable. When Horror films are released, they are sold to this demographic. The trailers are cut to please the guys and gals on the forums and fanboards who religiously say things like *Most Boring movie EVER UGH*. These are the most vocal supporters, and detractors, of any Horror franchise.

But what about the people who don't want franchises? What about the people who don't spend all of their time on forums? I suppose we just have to accept the extremes of the spectrum. Do I want to throw up when I go see Saw or do I want to fall asleep during Paranormal Activity 3? I don't want to do either, really. But, as politics has been split into extremes, so has Horror. We have liberal and conservative, and the moderates are the ones who suffer. Again and again.

It's not often that we get good Horror. It's sad really. But we can thank the few extremists who ruined it for everybody else.

Speaking of good Horror, I suppose I should let you guys in on my favorite Horror films of all time.

That's next in line, folks.

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Movie Review: Moneyball

Moneyball, based on Michael Lewis's bestselling book of the same name, is another one of those feel good sports movies about the drama of competition and the rewards that great sacrifice can bring. Except not really. Actually, Moneyball doesn't really make you feel that good. And it's not really even about sports. It's about creativity and adaptation. It's about having a bold vision and then following that vision until the end. Of course, that said, Moneyball is still the most exciting sports movie I've seen since Friday Night Lights.

In a way, Moneyball is a spiritual sequel to last year's great Social Network. Not only because Aaron Sorkin wrote both screenplays (Screenplays that Sorkin may win back to back Oscars with), but because they are about recent events that shook how we view our culture. While Social Network is about creative ownership and how we interact with one another in the twenty-first century, Moneyball is about adaptability and how creative, critical thinking can redefine a way of doing business.

The basic plot is this--Billy Beane (in one of Brad Pitt's most believable roles) is the general manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team. They have a tenth of the budget of the New York Yankees. He has just lost his best three players, and he has one season to save his job and the reputation of the team. At first, Beane counts on his scouts' old way of finding athletes to help find replacements for his top players. However, Beane finds out quickly that the way scouts find recruits feels more like a beauty contest than a search for raw athletic talent.

This is where Peter Brand comes in. Brand, played here by Jonah Hill in the absolute best, most subdued performance of his career, is an economics major from Yale who has created a formula for finding the most undervalued (i.e. cheapest) players in professional baseball, and using their abilities to get runs for the advantage of the team. At first, Brand's theories are labeled as ideological and naive. Like Mark Zuckerberg, Brand is young, brilliant, and totally misunderstood by the veterans surrounding him. However, Billy Beane is desperate for some new ideas, and he, much to the irritation of his peers, puts his full confidence in Brand's ideas. What results is the greatest winning streak in professional baseball history.

The film, directed by Capote's Bennet Miller, somehow makes guys sitting around talking the most exhilarating piece of filmmaking I've seen all year. The performances are understated and nuanced, allowing the audience to understand these men as a strange combination of professional gambler and businessman. Billy Beane is not played as a crusading genius, but instead as a broken, hopeless loner searching for a way to keep his job. When he isn't sitting quietly in his office, he is erupting in rage at whatever object he has around. Beane is terrified by Baseball, by his team, by his own ideas, and by Peter Brand's youth.

Brand, in turn, is terrified of being wrong. Although his ideas seem to be sound mathematically, he has a hard time feeling confident that the formula has a real-world application. This fear is amplified when the team, in the beginning of the season, has trouble finding its footing under the management of Art Howe, played by a thankless Philip Seymour Hoffman. Unlike Jesse Eisenberg's characterization of Mark Zuckerberg, Hill plays Peter Brand with with a completely opposite fault. He cares too much about those around him. He doesn't want to step on anybody's toes, and by empathizing too much with others, he has a hard time committing completely to his unorthodox ideas. Hill plays the role with a sort of hesitant politeness. He is quiet, always saying please and thank you, and is constantly moving out of other people's ways. The Jonah Hill you have come to love (or in the case of most people, come to hate) has made a total personality transformation for this film. His voice never rises above a whisper.

However, despite the excellent Sorkin screenplay and the excellent performances, Moneyball is truly Bennet Miller's film. From the opening shot of the film, it becomes quite clear that we are in the hands of a masterful filmmaker. The film is shot with a steady hand, only utilizing camera movement when it is of the utmost importance. The visual style, in its total lack of dynamic movement, is directly contrasted by the film's amazing use of sound.

There are hundreds of voices in Moneyball. At any one time, the voices of several sportscasters can be heard on the film's soundtrack. From the opening shot, the film is narrated by the voices of Baseball games. Voices act as the Greek Chorus here. In every major scene, over twenty voices speaking simultaneously can be heard over the somber image of Brad Pitt's face as he runs on a treadmill, listens to the radio, paces in his office. The voices represent the world's opposition of Billy Beane's ideas, and their omnipresence in the film lend to its unbelievable suspense.

Moneyball is an excellent film and I suggest you go see it as soon as possible. I challenge any of you to find a more compelling sequence in any film this year than "The Streak" sequence in the final act of the film.

I give Moneyball 9/10 well-behaved Jonah Hills.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Underrated: Life During Wartime